The Japanese aren’t alone in their appreciation for the maple tree, but they are unique in the strength of their spiritual bonds and aesthetic expressions which had already formed more than 1,200 years ago. On the other hand, there are the Canadians who adopted a new, national flag – the red and white with a red maple leaf – on February 15, 1965. Christopher McCreery says that the choice of the new flag was spurred on by certain extraneous events during the Suez crisis of 1956. I don’t know anything about that, but what I do know is that the Canadians had been discussing and arguing over the design of a new flag for decades. One frequently mentioned element would be the inclusion of a maple leaf or perhaps several. McCreery tells us that “The design that was ultimately chosen remained true to Canada’s heraldric traditions: it incorporated the national colours, red and white, as chosen by King George V, as well as a stylized Maple Leaf.” This leaf first appeared on Dominion coins in 1871. (The photograph of the flag shown below was placed in the public domain by Makaristos at wikimedia.org.)

Myself? I grew up – actually I never grew up – in Missouri and have fond memories of Aunt Jemima, pancakes and maple syrup. Pancakes are nothing without maple syrup. My mother made waffles too, but they were never very good. Sometimes they tasted like cardboard and all of the maple syrup in the world couldn’t save them. But she persisted. I guess she wasn’t going to stop until she got it right. She never did.

This is a photo I took last week in the parking lot of the complex

where I live. That’s not my car.

Momiji-gari 紅葉狩 – Viewing fall foliage as a spiritual/religious act

Whenever two American upper middle-class individuals or families meet each other for the first time – note my critical and somewhat elitist tone here – and they converse long enough eventually one will ask the other “Have you ever driven through Vermont ( バーモント) and New Hampshire ( ニューハンプシャー) in the fall? It is so beautiful.” Well, momiji-gari is the Japanese equivalent with one major exception: for the Japanese it is a truly spiritual experience on a level deeper or higher, depending on your point of view, than that normally felt by the Westerner driving through the low mountains of New England. Other than that there appears to be little difference between us on this matter.

The above image of momiji at Ginkaku-ji was place in

the public domain at wikimedia.org by Gribeco.

Bruce Feiler in his 1991 volume Learning to Bow describes making friends with a Japanese fellow who explained the background and significance of maple viewing to the Japanese: “Certain natural phenomena because of their splendor and singular beauty, developed almost a religious significance in ancient Japanese culture, where Shinto beliefs held that nature was the home of spirits who lived in the water, the land, and the trees. The mysterious transformation of green leaves into fiery reds and frosty yellows around the time of the harvest every year inspired awe among superstitious farmers. Just as a protocol around making tea… or painting calligraphy… so a proper form of viewing nature eventually evolved.” Feiler continued: “According to the Shinto code, the viewer on a proper leaf-viewing excursion should try to achieve a personal communion with the leaves, in a bond akin to the private communication between man and god at he heart of many Western religions. As Prince Genji once wrote to a lover, ‘A sheaf of autumn leaves admired in solitude is like damasks worn in the darkness of the night.’ By entering nature, one hopes to internalize the beauty of the leaves in one’s heart. Man enters nature, and nature, in turn, enters man.”

In the introduction to the book Japanese Maples: Momiji and Kaede by Vertrees (d. 1993) and Gregory it is noted that during the Edo period (1603-1867) up to 200 maple cultivars with poetical names existed. However, by the end of the Second World War many of these had been lost. Gardeners were forced to concentrate on food production and many rare, old and valuable maple trees were used for fuel during the war years. Generations of specialization were lost in no time to necessity.

Yet today maples, be they large, small or bonsai, are a must for every garden in Japan. “A standard garden book published in 1710 mentioned 36 varieties of Acer palmatum. By 1733 an additional 28 names were listed. An Acer list of 1882 numbered 202…” Vertrees believed that there must surely have been more than that which which were unknown to the list makers. An article in the July 2000 issue of Sunset said that today there more than 1,000 named varieties of the Japanese maple.

Vertrees said that both of the terms, momiji and kaeda, are used by the Japanese to “…indicate the maple species and cultivars.” Further on he said: “The word kaede stems from the ancient language term kaerude (kaeru, meaning ‘frog,’ and de, meaning ‘hand’).” The lobed leaf of the maple brought to mind the webbed ‘hands’ of the frog. The term was later shortened to kaede. At one time the term momiji may have been associated with a “baby’s pretty little hands.” How exactly this connection was made is unclear to me, but it is there nonetheless. Vetrees also noted that in ancient times there was the verb momizu which meant ‘to become crimson-leaved.’ According to him that morphed into momiji.

Momiji and the Tale of Genji: The Momiji no ga

The image shown immediately below is the crest identifying a specific chapter to the Tale of Genji. Each of the 54 chapters has been assigned one as a visual clue to what part of the tale is being represented. They are referred to as genjimon (源氏紋) and look somewhat like the modern bar code. Richard Lane and others put the number at 54 while Merrily Baird says there are only 52 which is the same number used in a Genji related incense game. Surely that is what she is referring to. Either way these mon can be extremely useful in identifying particular passages or sections of this story. They appear on innumerable Japanese woodblock prints. Sometimes they are placed in a cartouche in the upper part of a print or they are subtly or not-so-subtly displayed on robes or domestic objects. However, sometimes – and here is the cautionary note – they simply form a decorative element and have nothing to do with the original 11th century tale and some of them aren’t even among of the accepted 54 mon although they look like they are.

At the beginning of chapter 7 the Emperor is about to set out for the to the Suzaku Palace. This procession is the momiji no ga which is to take place after the tenth day of the tenth month. It was to be quite a production and was also an extremely rare event meant to celebrate a particularly important birthday such as the fortieth or fiftieth. Captain Genji, our hero, was to perform the dance of the ‘Blue Sea Waves,’ which he did and did brilliantly. His performance was said to be heavenly. Not only did he do it well, but his personal beauty and style made him as radiant as radiant can be. I think that probably explains the decorative cap shown in the image below. Maybe he would have worn such an item.

Royall Tyler in his brilliant translation of this tale says that momiji no go means ‘Beneath the Autumn Leaves’. Arthur Waley entitled the chapter ‘The Festival of Red Leaves’: “The imperial visit to the Red Sparrow Court was to take place on the tenth day of the Godless Month. It was to be a more magnificent sight this year than it had ever been before…” Seidensticker called it ‘An Autum Excursion.’ The variance in these three translations shows the fluidity of the Japanese language. Each gets at the sense of the moment, but each is also different from the other.

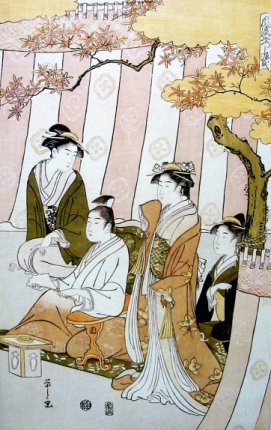

This is a detail from a triptych by Eishi illustrating the

momiji no ga. Notice the elaborate outdoor setting

with the use of temporary curtains.

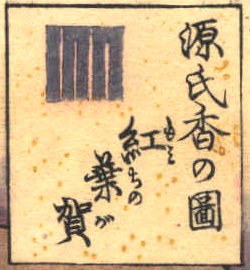

Now here is exactly the problem I have been talking about: The confusion over genjimon

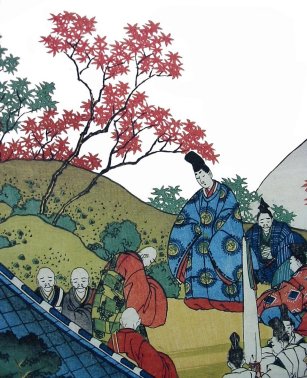

On October 20th Eikei (英渓), a great and generous contributor to my other web site, sent me this image by Toyokuni III showing Genji and his cousin Tō no Chūjō performing the dance of the “Blue Sea Waves.” Genji’s partner “…certainly stood out in looks and skill, but beside [him] he was only a common mountain tree next to a blossoming cherry.”

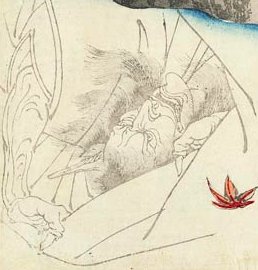

A detail close-up of the dancers hardly helps to distinguish one from the other, but the text is clear as to what the author intended.

And here is where the real confusion comes in. The title cartouche in the upper right of print clearly shows that this print is intended to illustrate the Momiji no ga chapter, but the genjimon is for that of Chapter 5, Wakamurasaki or ‘Young Murasaki’. Why? Was there a mix up at the publisher’s? Were they in a rush to get this edition out? Were they working from another text I am unfamiliar with. Who knows? Do you?

Momiji inspiring the poetic muse

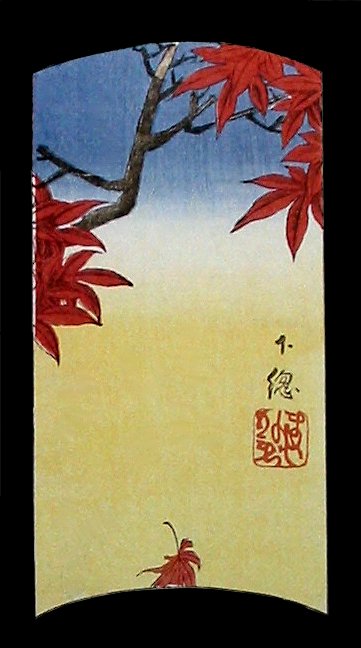

There are more poems in Japanese which mention momiji than could possibly be listed here. The image shown above is detail from a print by Hokusai which accompanies a poem from the Heian period. Composed by Fujiwara no Tadahira (藤原忠平 880-949) it relates the story of the Emperor Daigo visiting his father, former Emperor Uda who had abdicated, became a monk and moved to Mt. Ogura near Kyoto. Uda convinced Tadahira , the Chief Minister at the Imperial Court, to invite Daigo to visit his father during the fall when the colors would be particulary beautiful. No matter how one reads the Japanese the maple leaves are presented with an almost human sentience.

If the maple leaves

On the ridge of Ogura

Have the gift of mind,

They will longingly await

One more august pilgrimage.

小倉山

峰のもみじ葉

心あらば

今ひとたびの

みゆきまたなむ

Nancy G. Hume in her book Japanese Aesthetics and Culture points out that “By far the most common subjects of Japanese poetry are the cherry blossoms and the reddening maple leaves of autumn. If one were obliged to read through the twenty-one imperial anthologies between the tenth and fifteenth centuries, one would certainly end by being thoroughly bored with both cherry blossoms and maple leaves.” Great quote!

Momiji as a poetic reference by allusion

Hiroshige created the momiji image shown above. It is only a part of a larger print, but is known to represent the “Maple Leaves of Mama (真間) in Shimōsa (下総) Province”. That means that there is a world of information to be gleaned here, but few would understand that just by looking at these leaves. Actually there are whole worlds within worlds hidden within other worlds in most traditional Japanese prints and paintings. The Westerner could hardly be expected to see much more than what is laid out before him/her. However, a literal interpretation, no matter how pleasing, of an image is often just as superficial as what one sees on reality TV.

The “Maple Leaves of Mama…” refers to a series of poems in the Man’yōshū (万葉集 8th century) which relate the story of a beautiful peasant girl who was so sought after that she committing suicide by drowning herself. Near that spot at Mama in Kazushika a memorial tomb was erected. Nearby are maple trees which – as you can tell by now – burn a beautiful red in the fall. The tomb, the view and the trees became a pilgrimage destination. Although I am not sure if momiji are ever mentioned in the poems devoted to this woman red maple leaves immediately bring to mind her tragic end.

Momiji as a euphemism for eating venison

While researching this post I ran across a rather unusual quote about the Japanese and meat eating. It appeared in The Politics of Food by Marianne Lien and Brigitte Nerlich. “Historical evidence suggests that meat was widely consumed despite the existing taboo. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the shōgun himself, as well as other members of the political elite regularly received gifts of beef, and restaurants specializing in game were thriving. Nevertheless an aura of pollution surrounded the practice of meat eating. Reports make it clear that eating meat was something fairly unusual, and euphemisms, such as botan (peony), sakura (cherry) and momiji (maple) were used when referring respectively to the meat of wild boar, horsemeat and venison.”

Recently I watched a Harvard lecture on YouTube in which Professor Michael Sandel discussed the ethical issues around cannibalism. He described a shipwreck, desperate men, their rescue and a famous trial. The professor noted that one of them wrote an account and said that the morning they were rescued they were eating their ‘breakfast’. I don’t remember Professor Sandel’s exact words, but he did note that the man’s description was a euphemism if he ever heard one.

Note: I want to thank a sharp-eyed reader of this site for pointing out to me that momiji was used as a euphemism for venison and not horse meat as I had originally written. Thanks.

Momiji and the supernatural

In the Noh play Momijigari by Kanze Kojirō Nobumitsu (観世小次郎信光: 1435–1516) the hero wakes up next to what he thought was a beautiful young woman, but is actually a demon. The audiences would have known the story well, but the role of the oni was made more explicit by the fact that the demon is wearing or holding a hannya (般若) or she-demon mask. There is a painting by Torii Kiyoshige (鳥居清重) in the British Museum dating from ca. 1751-8 showing two actors in the principal roles of Momijigari. The actor playing the female/monster lead is holding a hannya mask.

© Trustees of the British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum

Below is an image of a print by Kuniyoshi showing the struggle between Taira Koremochi (aka Koreshige) and the demon of Mt. Togakushi. It was contributed to this post by my great friend Mike.

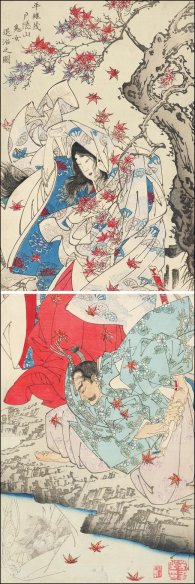

Momijigari is also the name of a kabuki “…dance drama by Kawatake Mokuami that premiered in 1887. While it is based on a nō play, it is not, however, performed in kabuki’s version of nō style. It uses a more conventional setting in which a large maple tree occupies center stage.” This is from The man who saved Kabuki: Faubion Bowers and Theatre Censorship in occupied Japan by Shirō Okamoto. (The three images from a vertical Yoshitoshi diptych shown below are also from my friend Mike. )

The play takes place during a leaf-viewing excursion on Mt. Togakushi (戸隠山). The hero, Taira Koremochi (平維望), and his men are hunting on the mountain when they come across a beautiful princess and her entourage holding a banquet. When they are invited to join the group they decline until the princess wins them. As Koremochi is falling asleep after drinking the wine offered by the princess he realizes that she is actually the demon in disguise so he kills her.

In another version Koremochi is separated from his men and runs across a group of maidens who are enjoying the Momijigari. He accepts their invitation to join them and drinks some of their rice wine and falls asleep. At that point the demons reveal themselves. However, the god Hachiman appears to Koremochi in a dream and gives him a magical sword. When our hero wakes up the sword is lying at his side and he uses it to kill the demons. The same thing happened in one of the versions of the tale of the monster Shuten-dōji.

In Light Verse from the Floating World: An Anthology of Pre-modern Japanese Senryū by Makoto Ueda there is a witty poem playing on the idea of the momijiri-gari and its seductive demon:

maple viewing

nowadays, the she-devil waits

at home

Why maple leaves?

Detail from a print by Toyokuni III with maple leaf motif on Takao’s kimono.

There is a series of kabuki plays which include the role of Ashikaga Yorikane (足利頼兼) and his love interest, Takao (高尾). Only one of these plays has the word momiji in it – as far as I know. As part of the costuming, more often than not, Takao is wearing something with maple leaves on it or has them as part of the decoration somewhere nearby. Yorikane is conventionally identifiable by a sparrow and bamboo motif. His obsession with his mistress means that he is neglecting affairs of state. For that reason Takao has to die.

The elaborate robes and hairpins or kanzashi (簪) worn by Takao indicate that she is from the highest rank of courtesans. In the Kunisada image detail below the actor playing her is wearing kanzashi with clearly defined maple leaves. In this case, these are the only momiji used to help us identify the role.

In another diptych by Kunihiro from ca. 1835 the artist portrayed Takao elaborately garbed, with kanzashi with maple leaf embellishments and a low screen with a momiji design.

![Kunihiro_Takao3[1d] Kunihiro_Takao3[1d]](https://printsofjapan.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/kunihiro_takao31d.jpg?w=351&h=416)

But wait a minute: Some Japanese prints on this theme like the one shown below by Kuniyoshi present no maple leaves on Takao and none nearby. While both Yorikane and Takao are wearing two different versions of the sparrow-bamboo motif his borders on near total abstraction. There must be a message here, but I don’t know what it is unless one can never be too careful when using visual cues.

I had no idea where I was going or what I am going to write about when I began this post. Now I am nearing an end and like all other topics there is much more to say, but maybe I will have to save that for another day. Thanks for staying with me this far.

For more information about Japanese prints and culture please visit our other web site at http://www.printsofjapan.com/.

Very interesting and wonderful article! I grew up in Montreal and I used to spend hours searching for the perfect red maple leaf when I was a kid. I still love autumn and falling leaves.

Comment by Connie Squire — October 26, 2009 @ 12:20 am |

I have been a student of Japanese for many years but never achieved the distinction of being able to practice it much. With difficulty and the help of friends and a Japanese pen pal of 30 years I can muster a translation.

Your website contains much interesting historical and valuable information about an aspect of language and culture that is hard to find outside of Wikipedia, to which I would never compare your website. Thanks for your persistence.

Comment by Ralph Cameron — December 6, 2010 @ 8:12 pm |

[…] Image found here: https://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/10/13/momiji-%E7%B4%85%E8%91%89-the-japanese-and-their-love-… […]

Pingback by Maple Leaf | Golden Giraffes Riding Scarlet Flamingos Through The Desert of Forever — June 16, 2013 @ 12:32 pm |

[…] Maple tree viewing (momiji-gari) has been a popular pastime since the eighth century. Maple tree viewing has spiritual significance, originating from the Shintō belief that all things in nature host spirits. The act of viewing and appreciating these trees is said to bring one into harmony with nature itself. For a much more detailed and interesting read about the symbolism of the maple in Japanese culture, see here. […]

Pingback by Wand Woods: Japanese Maple (Acer palamatum) – Mahoutokoro at Nagumo — December 10, 2018 @ 12:47 pm |

[…] is a fascinating discussion of this, and of the relationship between the Japanese maple and art, on the prints of Japan website, and I would like to quote just a smidgen […]

Pingback by Wednesday Weed – Acer (Japanese Maple) | Bug Woman – Adventures in London — December 3, 2019 @ 9:01 pm |