To begin with, I think you need to know that this post started percolating in my head because of research I was doing on a print in the Lyon Collection, which I will show you later. The print is the right-hand panel of a triptych entitled Sudden Shower at the Mimeguri Shrine (三囲の夕立). Like every other research project I set for myself I end up with more questions than answers. The first one was “What is Mimeguri?”

***

Years ago, in the 70s, I think, there was a BBC production called ‘Connections’ hosted by James Burke. It was scripted brilliantly and through it everything – even the most disparate elements – in the universe seemed to be interrelated in one way or another. In a more modern episode, one with laptops, it starts out with him saying: “This program is not just about India. It is about India and wine and war at sea and electricity and steam engines and love affairs and wallpaper and other stuff.” Exactly. That is what I mean. This post is not just about Mimeguri and the Washington Monument and the Lyon Collection, etc., and a bunch of other stuff. It is about everything which I find to be interconnected and fascinating. You’ll see.

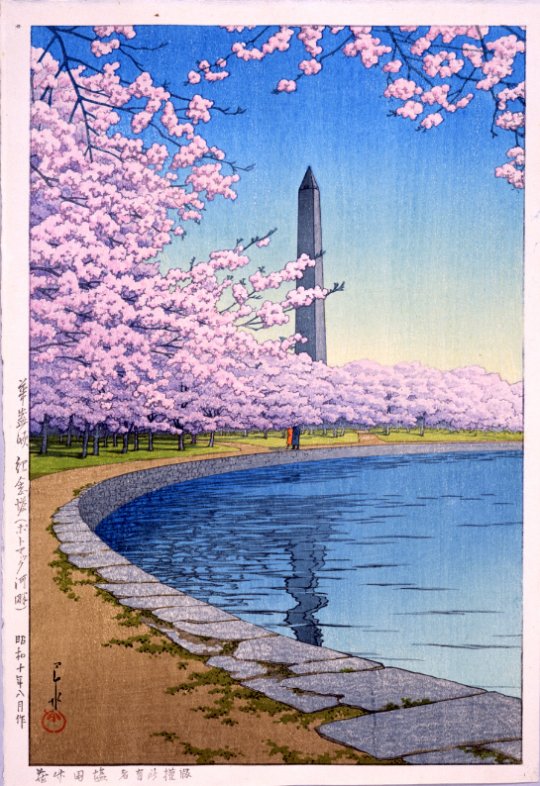

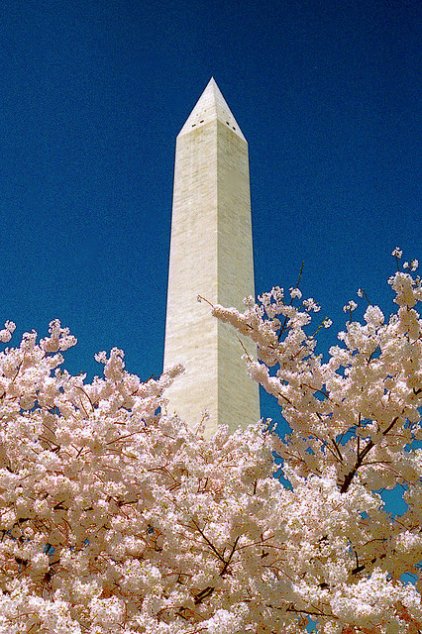

So, let’s get right to it. First I want you to see a modern(ish) print by Kawase Hasui done in 1935 of the Washington Monument in springtime. It’s lovely. (Don’t care if you agree with me or not. I say it is lovely and lovely it is. Traditionalists be damned.) The print is from the collection of Hagi University.

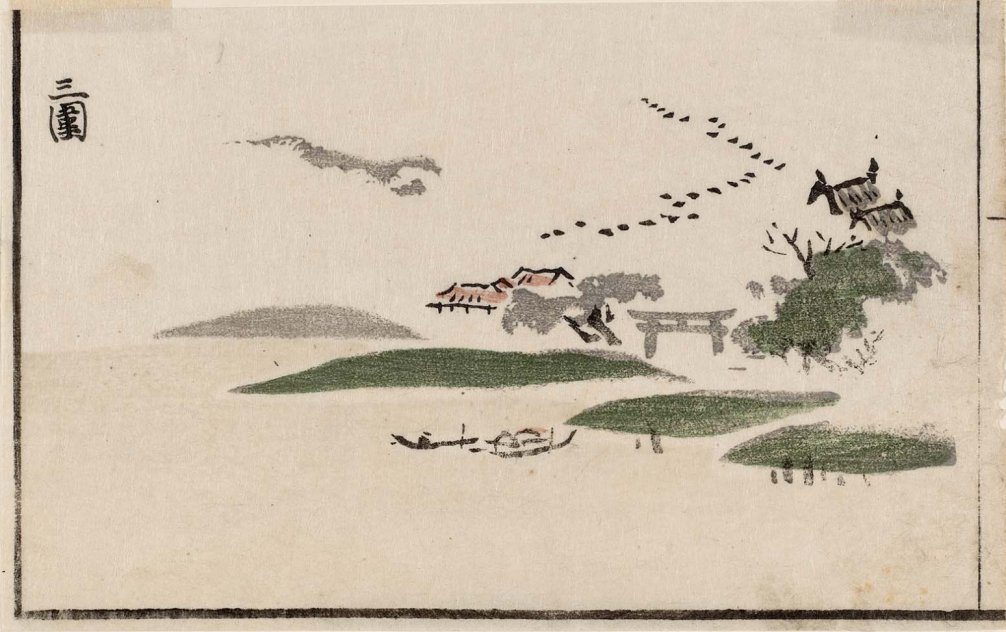

So, you ask, what in the hell does this have to do with Mimeguri? – whatever that is. Well, I will get to that soon enough. Be patient. First I will show you a Japanese book illustration from 1800 of the Mimeguri area and the Mimeguri Inari Shrine. It was designed by Kitao Masayoshi (1764-1824) and just look at how wonderfully modern and abstract it looks. Jack Hillier marveled that the printers could translate such a vaporous landscape into a reasonably objective printed image. This example comes from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

Notice the boats on the river in the lower center of the print. They are important. The river is the Sumida which runs through Tokyo, called Edo at that time. Notice the upright pilings to the right and the horizontal, green, blobish hills – which is really an artificial embankment, the torii gate – the indication that this is an entryway to a sacred site – and the brownish-red rooftops of the shrine structures in the center and off to the right the more formalized gray tiled rooftops. Above these is a flight of geese. This will come up again later, too. It is only one of many favorite motifs related to the Mimeguri Shrine. Why? I haven’t a clue as of now, but if I find out you will be the next to know.

By the way, I know that ‘blobish’ is not a real word, but I like the sound of it and I assume you get what I mean: having the qualities of a blob.

So where does the name come from?

The word ‘mimeguri’ means three circles or turns. Inari (稲荷) means fox. It is said that once upon a time a statue of an old man astride a white fox was found buried beneath the shrine itself. The fox came to life, spun around three times and then disappeared. Below is a humorous print by Yoshitoshi from 1881 showing foxes bewitching humans at that shrine. This is something they were known to do frequently there and elsewhere in Japan.

Notice that the characters identifying the shrine are attached to a signboard hanging from the from of the torii.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

Where is the shrine located?

The shrine is located on the left bank of the Sumida River across from the Asakusa district on the right bank. During the Edo period townspeople would sail up the river on their way to the Yoshiwara pleasure district. A huge embankment, the Bokutei, was constructed early in the 17th century. It protected the shrine and restaurants and teahouses and low lying farmland from floods. Visitors to this area would disembark from their vessels and climb stairs leading up the Bokutei and then climb down again to reach their temporary destinations. That is why only the top of the torii, when seen from the river, appeared to have sunk, even though it hadn’t. Look for this in the images I am going to show you. One more point: the Bokutei itself became a destination in the spring because someone came up with the idea of planting it with cherry trees. Hence, the connection to the cherry trees now seen along the Potomac in Washington.

http://www.mfa.org

http://www.mfa.org

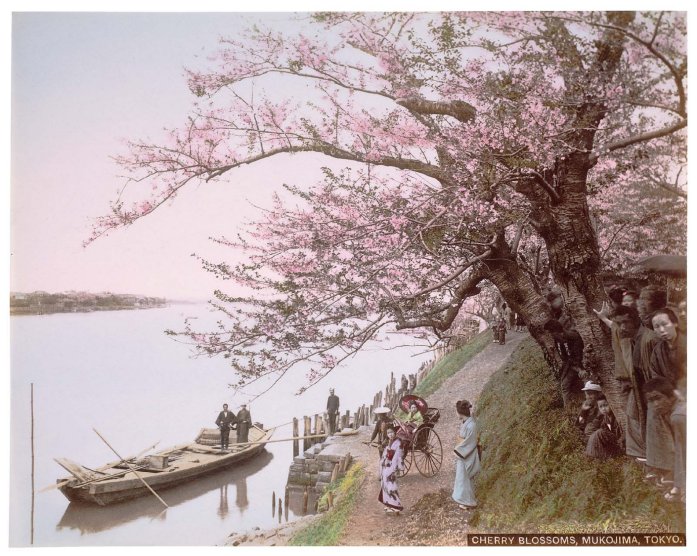

View of the embankment, the Bokutei, along the Sumida in the Mukōjima district near the Mimeguri Inari Shrine. This dates from ca. 1895.

There are loads of stories about some of the early shoguns and falconry. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the one man most responsible for importance of modern day Tokyo, was said to lived elsewhere but would visit Edo (the former name of Tokyo) often on the excuse that he was going on falcon hunts. And where were these hunts? In the marshy land that was eventually to be called Mukōjima (向島), the island over there.

New York Public Library

New York Public Library

“Among the gardens of Mukōjima and among all the people whose names are linked to the area, there is one that stands out : that of Sawara Kikū [佐原鞠塢], a retired antique dealer with a flair for publicity and a wide circle of friends… In 1802, he opened a garden to the public just behind the Bokutei embankment. He and his friends, planted plum trees and an assortment of flowers and grasses in the garden.

The sacred quality of the banks of the Sumida at Mukōjima was brought to symbolic fruition when Sawara Kiku and his friends devised a pilgrimage route to the Seven Deities of Luck, Shichifukujin. This was only the second such pilgrimage route in the city, the other being (appropiately [sic] enough) across the Sumida on the Suwa Bluff. The pilgrimage route introduced an explicitly religious note : one could make an imprecation to Daikoku and Ebisu at Mimeguri Shrine, to Benzaiten at Chomeiji, and so on. The idea was immensely successful. The bonhomie and the serenity of spirit of the Seven Gods, and the lack of metaphysical speculation involved, conspired to intensify the popular appeal of the area.” (This is quoted from ‘The Sumida: Changing Perceptions of a River’ by Paul Waley.)

It should also be noted that the dramatic effect of the blossoming cherry trees suffered terribly as the surrounding area succumbed to rampant industrialization and its concomitant unhealthy outpourings of toxic fumes. It has been said that “It was in the end industrial pollution that did most harm to Mukōjima as a place of recreation. The flowers and trees, including the cherry trees of the Bokutei, wilted under the fumes by a forest of factory chimneys. The gardens suffered too.” As if this weren’t bad enough, there was also the devastation wreaked on this part of Tokyo as a result of the horrific earthquake and fire of 1923. Of course, after that came the bombings of the Second World War. It is amazing anything has survived at all.

The firebombing of the Mukōjima area in March 1945

as remembered by Katsumi Hidesaburō.

Mukōjima was slow to enter the consciousness of the Edoites – Mukōjima developed long after its sister district, Asakusa, on the west bank of the river. While Asakusa was becoming a major destination rice was still being planted in much of the Mukōjima area. Waley wrote:

In the evolution of the banks of the Sumida at Mukôjima as a place of recreation and release, one of the most important developments was the planting of cherry trees by the eighth shogun, Yoshimune, in the 1720s. Maeda Ai refers to the creation of “official parks,” and suggests that it was not for another half a century at least that these areas were accepted and brought into the cultural idiom of the people of Edo… The cherry trees are described with charming but conventional hyperbole by Hiroshige in the commentary to a print in his Ehon Edo miyage series : “The Yoshino cherry trees were planted, it is said, on this never-ending embankment in the longpast [sic] Kyoho era (1716-36), but even now in the Third Month they continue to blossom like clouds or like snow, surpassing in appearance even the domain of the sages.

Was the old Mukōjima doomed?

Waley also wrote:

What happened to cause the transformation of the Sumida’s banks at Mukōjima, once so beloved of the inhabitants of the city? First there was Mukōjima’s position just north of Tokyo’s burgeoning industrial zone of Fukagawa and Honjo. Proximity made the northern sweep of industrialization all but inevitable. Besides, the temples, shrines, and gardens of Mukōjima were all small and not monuments of civic importance or aesthetic distinction. They belonged to a popular culture that had been shunted aside in the new national polity and snubbed by the framers of a new religious consciousness. Municipal planning envisaged different forms of recreation for the citizens of Tokyo. The municipal leaders eventually turned their attention to the banks of the Sumida, creating a public park, Sumida Kaen, in 1923 on the south side of Kototoi Bridge… But a municipal park belongs to the world of monumentality, of artificial preservation, of deliberate intellectualizing, and of the fencing in of nature – all that stood opposed to the spirit of Mukōjima and the Bokutei.

By the time Mukōjima was officially incorporated into the city of Tokyo in 1932 one publisher led off with the heading: “The Metropolis’s Proud Factory Zone – Where Memorial Stones Engraved with Poems Art Turned Black by the Soot”.

Early etchings in Japan

Among the earliest known prints of the Mimeguri embankment are two rather odd, non-traditional etchings by artists who had been studying European prints and had learned their craft from foreigners, Dutchmen, in the port of Nagasaki. The first practitioner was Shiba Kōkan (司馬江漢: 1747-1818). His first copperplate etching is of the Mimeguri. It dates from 1783. If you look closely in the distance, about midway, to the left, I think you can see a torii and the entrance to the grounds of the shrine. It should be noted that: “Because the etching was made for a peep-show box, left and right are reversed.” This explains why the Kōkan print seen immediately below is reversed from the image by Denzen shown below it.

Another etcher from this period is Aōdō Denzen (亜欧堂田善: 1748-1822) also studied Western art in Nagasaki and like Kōkan is thought to have learned his craft from the Dutch. There is one of his etchings at the Tokyo National Museum showing basically the same scene, but with a very European feel to it – including an unfurled banner in the sky and a very un-Japanese looking fellow walking a horse. The torii appears here, too, partially hidden behind the trunk of a tree.

Tokyo National Museum

Tokyo National Museum

Just for those of you who don’t know, European-style etching never quite caught on. At least not at this early date. It took more than 100 plus years before Japanese artists tried this again. However, it is the exoticism of these prints which helps explain their rarity.

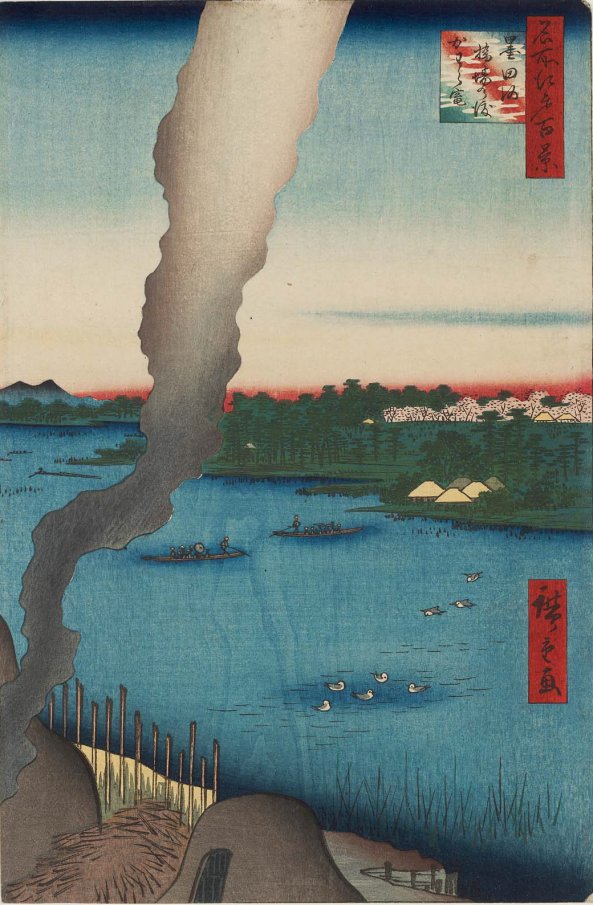

Did you notice the smoke rising in both of the etchings seen above? It came from the tile kilns near the Hashiba-no-watashi ferry on the Asakusa side of the river. Below is a print by Hiroshige. The perspective shows the Bokutei of the Mukōjima side with its cherry trees in bloom.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

What could be more subtle than this print?

Below is a print by Kunisada from ca. 1823 from the series Mirror of Fine Views. This one is entitled ‘Mimeguri’ (三廻). Again we see the smoke rising from the kilns located on the Asakusa side of the river and again we are looking across to the embankment of the Bokutei and the Mukōjima district.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

Now, just because I find this interesting, too –

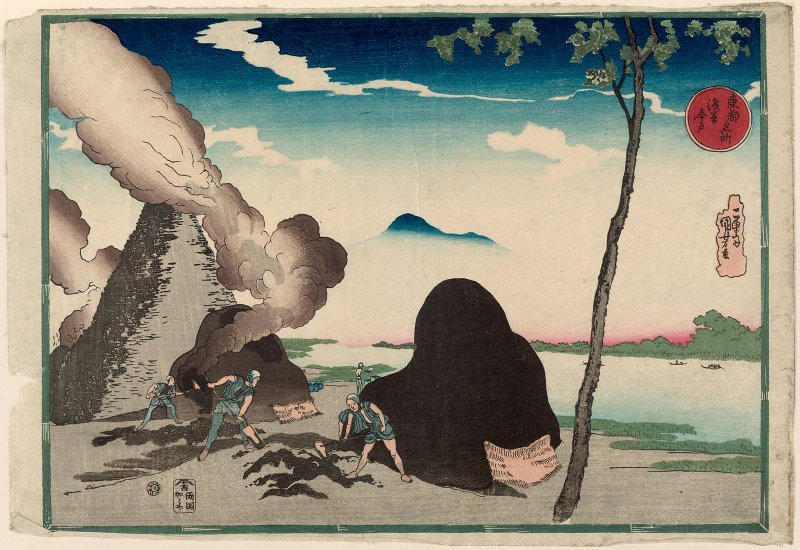

Since I didn’t really no much about the tile kilns in Edo – okay, I didn’t know anything about them – I decided to do a little more digging and a couple of surprise came up. I had long known the Hiroshige print which I posted above and I knew of another print about kilns by Kuniyoshi, but didn’t realize they were the same place – but with a totally different feel to it. And there is still more: another Aōdō Denzen etching. Whoopie! Turns out these kilns were located in the Imado (今戸) part of Asakusa, to be a more specific. Below is Kuniyoshi’s version followed by Denzen’s.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

That large grey pile on the left which towers over the kilns and the workers is made up of pine needles which were used to fuel the fires. Mount Tsukaba looms in the background. This print dates from ca. 1834, about 24 years before the image by Hiroshige. The etching by Denzen is from even earlier since we know that he died in 1822. Note that this print has been trimmed down. Originally part of the print showed a fringed border. Denzen did a number of these. Kind of like a placemat.

“What was so intrinsically special about this stretch of the left bank [of the Sumida River]? Nothing, really. There was nothing beautiful about the scenery here : no waterfall, no lake, no exciting prospect. There were no hills. The terrain was flat and swampy. There were no landmarks and no famous buildings. This was new country. It was not Kyoto. But for all that, it found an inalienable place in the affection of the inhabitants of the city. In essence, there was but an embankment situated for most of its course about one hundred meters inland and built, records tell us before 1658. Known as the Bokutei, it was lined with cherry trees, peach trees, and willows. Along it ran a path. It stretched from Mimeguri Shrine in the south… to Mokuboji in the north… and on round to Senju Bridge. One or two restaurants, among the city’s best known eating establishments, were to be found along the river bank… Tea stalls lined the embankment, especially during the season of blossoms. Gardeners and nursery men too had stalls there, and seem to have been much in demand.” (This is quoted from Paul Waley.)

Now here is the print from the Lyon Collection that got me started on this voyage –

Click on this print by Kunisada to learn more about it. Look at those colors, the freshness, the clarity. Amazing. If only all traditional Japanese prints had survived in such conditions. Below is another small reproduction of the full triptych that this example comes from. It too is in the Lyon Collection, but is no where near as pristine as the one shown above.

Click on this print by Kunisada to learn more about it. Look at those colors, the freshness, the clarity. Amazing. If only all traditional Japanese prints had survived in such conditions. Below is another small reproduction of the full triptych that this example comes from. It too is in the Lyon Collection, but is no where near as pristine as the one shown above.

The question now is: What is behind the story of a group of women getting caught in a rainstorm on their way to the Mimeguri Shrine?

Kunisada’s triptych dates from the mid-1840s. It was preceded by another triptych by Kiyonaga (清長: 1752-1815) on the same theme, but from the late 1780s. Why? The answer appeared in the 1916 Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. “Men and women are seeking shelter in a gateway. Above, in the clouds, the demons of a thunder-storm are conferring over a haiku (a short poem in seventeen syllables) composed by the Japanese poet, Takarai Kikaku (宝井其角: 1661-1707).

The reference is to a tradition that on the 28th of June, in the year 1693 Kikaku went with his disciples to the Mimeguri Inari Shrine, at Mukojima, Tokyo, where, to his surprise, he encountered a crowd of highly excited farmers. Upon inquiry he learned that they had been praying for rain to terminate the long drought which threatened their crops with ruin, and in response to suggestions from his companions, coupled with the persistent appeals of the farmers, – who, because of his bald head, mistook him for a Buddhist priest, – he composed the following haiku, which he recited with great earnestness before the altar:

三囲神社関係文書

Mimeguri jinja kankei monjo

‘If thou art indeed the God who watched over farms, send forth, I pray, thy showers!’

Another possible translation is:

Shower the field

With the grace of the kami of Mimeguri.

To the great delight of all this prayer was instantly answered, and the nourishing rain descended in torrents. The Japanese expression meaning ‘watch over,’ as used in the foregoing poem, is mimeguri, a homonym of the name of the Shrine. Such plays upon words are a marked characteristic of Japanese poetry.”

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

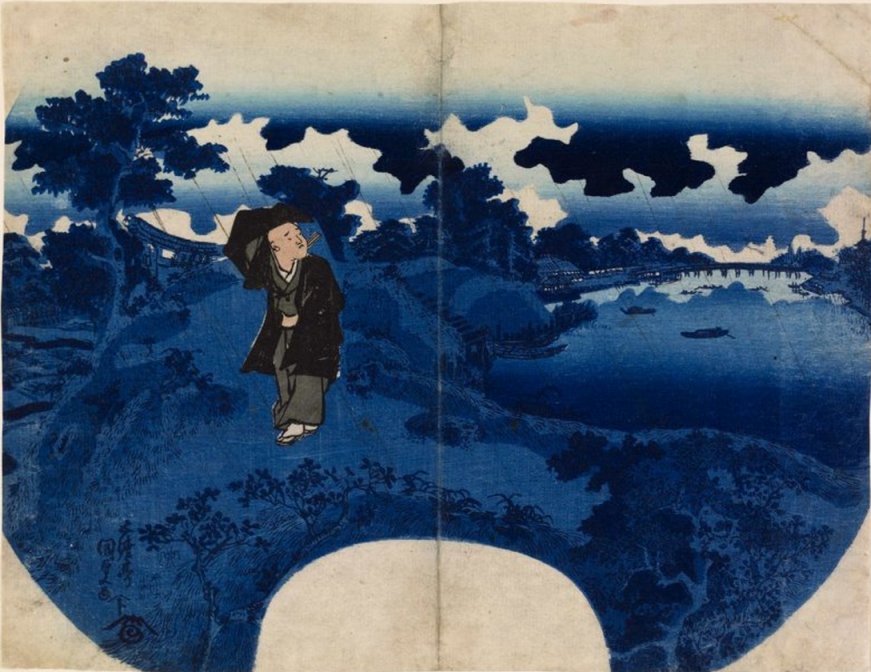

There is a Kunisada fan print, dominated by the newly imported Prussian blue dyes, dating from 1831. It shows Kikaku, standing on the Bakutei, trying to protect himself from the rain. The torii leading to the Mimeguri shrine can be seen behind him and slightly to our left.

The Achenbach Foundation

Sometimes it isn’t rain, but snow…

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

One has to wonder what Kunisada must have been thinking when he created the stunningly beautiful triptych from the 1820s shown above. Was the snow and the visit to the Mimeguri Shrine the central point he was making or was the setting simply a vehicle for exhibiting beautiful and sexy women in their finest clothes on a winter outing? I vote for the latter.

Of course, such works as you have already seen had their precedents. In fact, Kunisada’s teacher Toyokuni I produced more than a decade earlier an equally beautiful triptych, The Twelfth Month, Snow Falling on Mukojima. based loosely around the same theme. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston owns a very fresh copy of that triptych’s left-hand panel.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

And Toyokuni I was following in the traditions set by Kiyonaga. Here is a single panel, the one on the left, from 1788 from what was most likely a triptych. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has what appears to be the center and left panels.

Carnegie Museum of Art

Carnegie Museum of Art

A Teachable Moment…

There are complete copies of the full triptych of …Snow Falling on Mukojima viewable on the Internet, but none that I have found that have the full-on crispness of the colors of the examples seen above. All of the others are a bit tired, worn and faded. I am going to show you below the left-hand panel from the collection of the National Diet Library as a lesson for those who aren’t fully versed in the connoisseurship of Japanese woodblock prints. Comparing these two examples should speak volumes.

National Diet Library

National Diet Library

As you can see the second example is considerably faded, soiled and distressed with some paper losses at the top and upper left side. This raises a number of questions. What makes this print important and desirable even in this tired condition? I’ll tell you or try to: 1) It was designed by Toyokuni I, a great artist and draughtsman; 2) older traditional Japanese woodblock prints are rarely found in mint condition. In fact the one in Boston is probably even a bit off from the vibrancy it exhibited at the time it was first offered for sale; 3) sometimes the elegance of a print lies more in the subject matter than it does in its coloring. Different editions of the same print often show different colors and often later editions are not printed with the same care and concern for the more judicial aesthetic side. Not that I am saying that I know of other editions of this triptych, but in many cases the commercial success of first printings almost demanded later (and lesser) editions. 4) Rarity. Have you ever seen it before and do you think you will ever see it again if one of these is offered to you for sale?

Scroll back and forth between these two examples and study each little area. It will be very instructive for those who don’t already know this truth about Japanese woodblock prints. One other more subtle thing to notice here is that the falling snowflakes seen against the gray of the sky don’t show up floating by the colorful clothing of the three women. You might say: “Why should they when the women are sheltered by their umbrella?” Well, I’m sorry, but that can be the reason. It has more to do with artistic license. The snowflakes don’t show up against the top of the gray stone torii seen in the middle right of this panel. The background is more like a stage set – a scenic backdrop. Not only that. Look at how the snowflakes are made. They aren’t printed. They aren’t printed at all. In fact, all they are is little spots of void in the printing, i.e., they are the color of the paper this image is printed on. The gray of the sky is printed around them. They hold no ink.

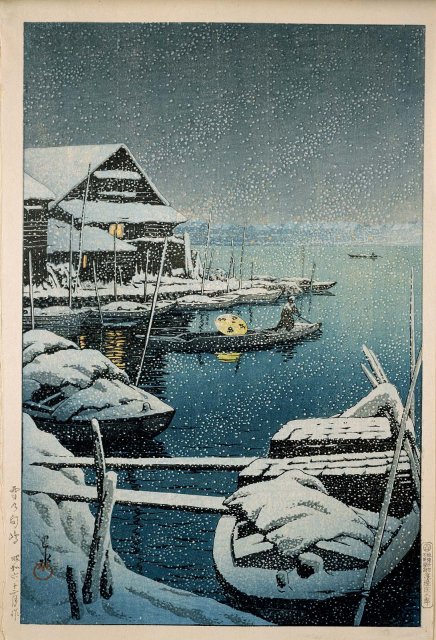

Before we leave the subject of snow falling at Mukōjima let’s look at one more example by Hasui from December, 1931 – Snow at Mukōjima. At first glance it appears to be more prosaic then the examples of works by Toyokuni I and Kunisada. But, from my point of view, Hasui is almost never prosaic. The themes may seem more mundane, but… Besides, by 1931 Mukōjima had undergone many dramatic changes. Not only was there extensive urbanization and modernizing, but there had also been that devastating earthquake and subsequent fire which had done a job on that part of Tokyo.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

Seen from the riverside only the top of the torii was visible –

There have been a number of authors who have noted that the top of the torii leading to the Mimeguri Shrine in Mukōjima, as seen from the Sumida or from the Asakusa side of the river, appeared to have been sinking. Even prints and paintings showing visitors walking along the top of the embankment, the Bokutei, give somewhat the same impression – especially for those unfamiliar with the lay of the land.

“From the water, only the crossbars of the shrine gate could be seen… It looked only high enough for an animal [like a fox] to slink through.”

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

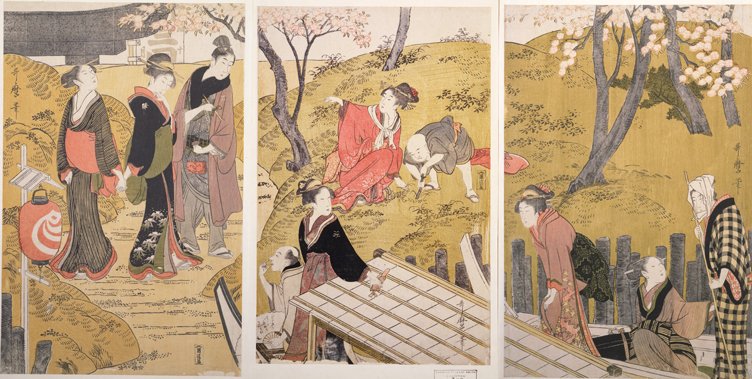

This triptych from 1799, The Display of Treasures at the Mimeguri Shrine, shows a group of people “…out to view the cherry blossom[s]. They are walking along the embankment of the Sumida River at Mimeguri Shrine, during the period of the display of shrine treasures in 1799. On the right sheet a tipsy woman has dropped something from the breast of her kimono and the people around are laughing.” (Quoted from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro by Shugō Asano and Timothy Clark, #329, vol. 2, p.206.)

There is another triptych, The Embankment at Mimeguri, by Utamaro that was published in the same year, but by a different publisher. It is housed in the collection of the New York Public Library. Is it a companion piece? Very possibly. The lantern in the left panel has a flaming jewel motif on it. However, there is another version of this triptych in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum and on that one the lantern shows the characters for ‘kaichō’ or ‘display of treasures’. Clark and Asano believe that one to be the earlier edition.

At the top near the right end of the torii is a banner which indicates that the shrine is celebrating the display of treasures. The same is true of the first Utamaro triptych where the lettering on the banners is much more readable. In that one the banner on the left reads ‘Mimeguri’. In the center panel of the triptych below is a man who is holding a fan which has inscribed on it a poem: “As far as the eye can see -/Excited cherry blossoms/Dancing on the river.” That last phrase about dancing is based on the fact that the blossoms would have been reflected in the Sumida.

New York Public Library

New York Public Library

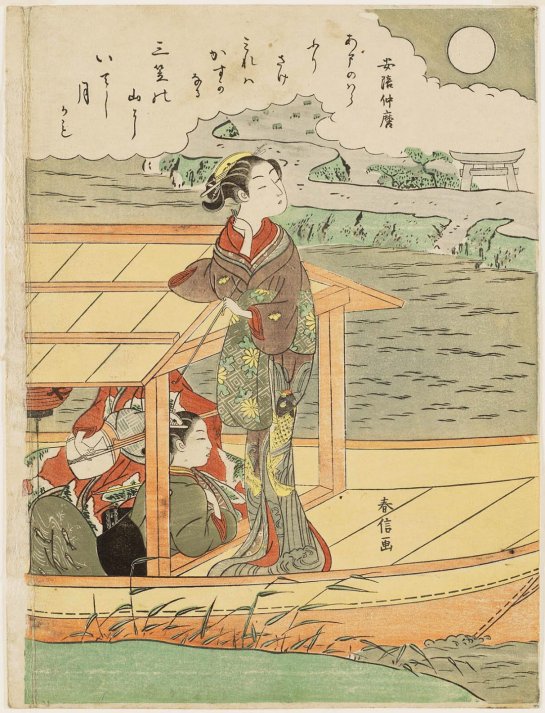

In Boston there is Harunobu from ca. 1768 of “A party of courtesans or geisha… on a boat in the Sumida River, opposite the torii of the Mimeguri Inari-sha.” In the clouds above there is a poem by Abe no Nakamaro (698-770). Above the torii is the moon, which is the point of the poem. Nakamaro had traveled to China and was composed on seeing the new moon there. It was the poetry of yearning, of homesickness. And yet in the end he realizes that the same moon he is seeing there is the same one that is shining on his homeland.

When from afar I

descry the plains of Heaven,

I realise the same moon has come out on Mount

Mikasa at Kasuga.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

In 1768 the Yoshiwara, the licensed redlight district, was destroyed by a fire and the courtesans were relocated to Matsuchiyama, right across from the torii at Mimeguri. Perhaps these young women are yearning to return to their old home, like the poet who wanted to return to his a thousand years before.

An 1854 Toyokuni III print of a beauty fishing from a dock on the Asakusa side of the Sumida still gives us a good view of the landing site and steps up to the embankment on the other side of the river and over which can be seen the top of the torii.

National Diet Library

National Diet Library

An interesting curiosity –

There is a Hiroshige fan print at from the mid-1840s that at first glance gives the sense of looking through a window on the Asakusa side of the river toward the Mukōjima side. But it isn’t a window. It is a painting mounted on a hanging scroll. The curatorial files at the Victoria and Albert Museum state: “This elegantly composed uchiwa-e, or rigid fan print, design by Hiroshige has survived in good condition despite having been salvaged, as the ribmarks on its surface indicate, from a made-up fan. It consists of a close-up view of a flower arrangement in front of a painting mounted as a hanging scroll such as might be found in the ‘tokonoma’ or display alcove of a Japanese room. In this case the chill of winter is portrayed by a snowy view of the ‘torii’ gate of the Mimeguri Shrine seen across the reaches of the Sumida river in Edo (modern Tokyo). The starkness of the image is relieved by the curving form of the narcissus on the right and the deep red of the camellia on the left. The artist’s signature appears to be appended to the painting rather than to the print as a whole. This was a common contrivance in compositions of this kind.”

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

But what about the view from the other side of the embankment?

If you look carefully at this print by Eisen which emphasizes the angularity of the torii you will notice the temporary structure constructed for a tea stall built “…especially during the season of blossoms.”

Tokyo National Museum

Tokyo National Museum

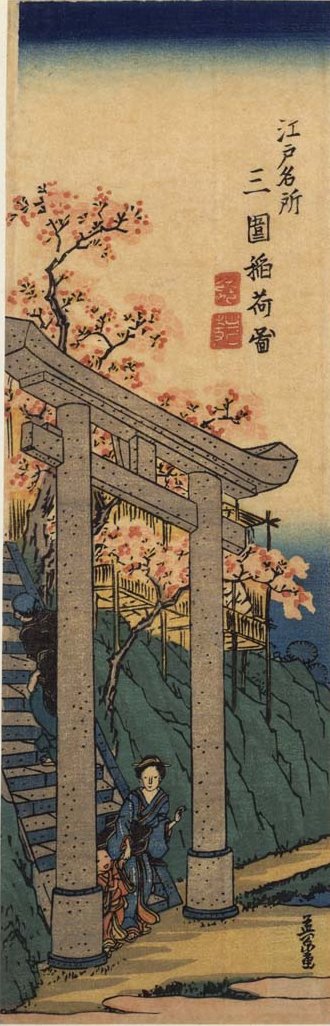

The beauty of this one – The great thing about this left-hand panel of a triptych by Kiyonaga from ca. 1787 is that you get a great sense of the view of the shrine and its entryway as seen from the Mukōjima. There is the embankment, the stairs down, the first torri, the walkway to the second torii and the front of the shrine itself on the far left. Wow!

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

Do you know what a votive tablet is?

People bought and gave votive tablets or ema to shrines and temples. They were paintings on wood and generally had something to do with the particular shrine, the donor or the gods they were imploring to bring good fortune. Below is a Bunchō print from ca. 1769-70 from the collection in Boston. It shows a man looking up at an ema of an actor hung up at the Mimeguri Shrine. The plaque even hangs in front of a long, horizontal sign that shows in the lower right the top of its torii. We know it is Mimeguri because it says so in the bottom characters nearest a banner close to the torii.

www.mfa.org

www.mfa.org

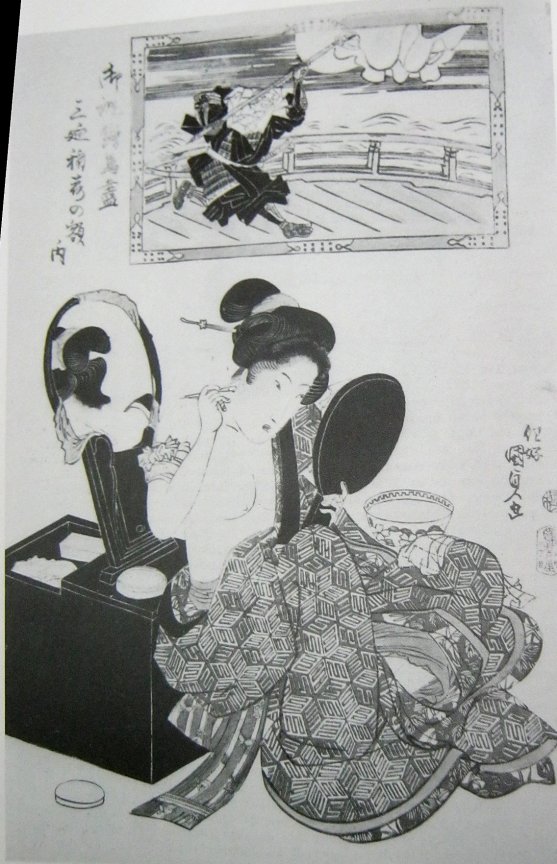

Breaking the protocol! Protocol? What protocol? Well, I have a personal and unwritten one that says I should never, or almost never, use images of prints reproduced only in black and white. They just don’t have enough pizzazz, if you know what I mean. However, there are always exceptions and rules to be broken and this is one such example.

There is a series of prints by Kunisada from the early 1820s showing a framed votive plaque at the top of each one. The print which pairs a beautiful woman applying white powder to the nape of her neck and an ema of Benkei in his battle on Gojō Bridge is related to the Mimeguri Shrine. How do we know this? First off, the inset image of Benkei is in a frame like those of other votive plaques and the title of the series is On-atsurae ema zukushi. The title of this particular print is Mimeguri Inari no Gaku no Uchi.

There is a color image of this print shown in a exhibition of tattooing at the Musée du Quai Branly. I believe it comes from a blog posted by Adriana Sanchez. As best I can tell, it is being shown in this museum of an example of a woman who is trying to cover up a tattoo devoted to an ex-lover. Below is another breach of one of my self-imposed rules: I have borrowed her photo from this show so you can get a sense of the coloring of this print. Whether I agree with the information provided or not is another matter altogether.

Posted originally by Adriana Sanchez.

Posted originally by Adriana Sanchez.

Eliza Scidmore – don’t pronounce the cee – was the moving force behind the cherry trees along the Potomac basin –

I found this at commons.wikimedia. It is by Rizka.

I found this at commons.wikimedia. It is by Rizka.

Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore (エリザ・ルアマー・シドモア) was born in 1856 in Clinton, Iowa and died in 1928. She attended Oberlin College. In 1884 her brother, George Hawthorne Scidmore (1854-1922), a lawyer who went to Japan to join the diplomatic corps. She visited him and on her return to Washington, D.C. in 1885 she began lobbying for the planting of cherry trees along the Potomac. It wasn’t until years later that, after enlisting the support of the first lady, Helen Taft, that the project was realized. That was in 1912. Scidmore was determined to “…see a ‘Mukojima on the Potomac’…”

Scidmore was remarkable in more ways than you can imagine. She had a fuller and more adventuresome life than that of most men I have ever met. She wrote society columns for newspapers early on. Not a very manly occupation, but wait… With the money she saved up from that job she took a trip to Alaska in 1883. From that came a book on her travels there and even had a glacier named after her. She brought the word ‘tsunami’ into the English language. She was one of the first – if not the first – female member of the National Geographic Society and even joined its board of directors in time.

One of Scidmore’s beautiful hand-colored photographs.

One of Scidmore’s beautiful hand-colored photographs.

Scidmore’s love of Japan was so great that she returned there in 1923 to live out the rest of her days. When she died her ashes were buried in Yokohama “…under a springtime carpet of pink and white petals.” In 1891 when she published her account of one of her visits to Japan, Jinrikisha Days in Japan, she started out by quoting St. Francis Xavier (セント・フランシス・ザビエ: 1506-1552): “I cannot cease from praising these Japanese. They are truly the delight of my heart.” By the time she had written this book Scidmore had lived in Japan for three years, “…while many weeks were spent in Kioto, Nara and Nikko.”

There was more than one famous spot in Tokyo to view cherry blossoms. Scidmore wrote: “The cherry-blossom Sunday of Uyéno Park is a holiday of the upper middle class. One week later, the double avenue of blossoming trees, lining the Mukojima for a mile along the river bank, invites the lower classes to a very different celebration from that of the decorous, well-dressed throng driving, walking, picnicking, and tea drinking under the famous trees.”

There is no question that Eliza Scidmore was a Japanophile, but… she was a bigot, too – at least, when it came to other Asians. She made this clear in her writings:

To appreciate Japan one should come to it from the main-land of Asia. From Suez to Nagasaki the Asiatic sits dumb and contented in his dirt,

rags, ignorance and wretchedness. After the muddy rivers, dreary flats, and brown hills of China, after the desolate shores of Korea, with their

unlovely and unwashed peoples, Japan is a dream of Paradise, beautiful from the first green island off the coast to the last picturesque hill-top.

The houses seem toys, their inhabitants dolls, whose manner of life is clean, pretty, artistic, and distinctive.

Below is another photo of the Washington Monument framed by blossoms. I am posting it because I find it so striking. It was posted at Flickr by Jeff Kubina.

I am not exactly positive about this, but… While doing research on one particular Japanese print artist, Hokuei from Osaka, I was looking through a catalogue of prints from the collection in the Philadelphia Museum of Fine Arts, compiled by Roger Keyes and his wife, when I just happened to notice this entry toward the back:

Mimeguri Inari Shanai Kuniyoshi Shachū Himen

三圍稲荷社内国芳社中庇免

1873

“A memorial monument for the artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi erected at Mimeguri Shrine, Tokyo; quoted in Kuroda, Kamigantae Ichiran (pp. 159-60). The following Osaka print designers are mentioned on the memorial: Naniwa Yoshiume, Yoshiharu (pupils of Kuniyoshi); Yoshiyuki, Yoshitoyo, Yoshinobu (deceased pupils of Kuniyoshi); Umeyuki, Yoshimune, Yoshihide, Umeharu, Yoshitaki (pupils of Yoshiume); Yoshimitsu, Yoshikuni (pupils of Yoshitaki [?]).

That is what led me to search out the image I am posting below. I think it is that Kuniyoshi memorial at Mimeguri.

*****

For those of you who would like to see more information about Japanese art and culture please visit my other web site at http://www.printsofjapan.com.

For a ton more information – scattered and diverse – visit my index/glossary pages. You will find links to numerous individual pages about half way down the home page. Just click on any of them and then brace yourself. Enjoy the ride! Thanks!

Wow. Beautiful. Thanks for sharing all of this with us.

Comment by toranosuke — February 1, 2015 @ 8:17 pm |