Before I throw myself into the deep end of this pool you need to know that I can’t swim. Like every other topic I approach basically I know next to nothing. Everything is a great adventure. Bear with me through the rough spots and soon both you and I will know a lot more about this guy. At least, that is my hope.

Let’s start with this gorgeous Edo period, polychromed, wooden sculpture of Bishamon standing on top of a blue demon. It comes from the British Museum collection and represents Bishamon as the Guardian King of the North.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The detail shown below is from a Meiji period painting of Bishamon. It was purchased by Patdem and posted by him at commons.wikimedia.org.

A little history – Mimi Hall Yiengpruksawan in a 1998 publication of the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies said that Bishamon has his origins primarily in Central Asia and not India. He emerged in the sixth and seventh centuries as a militant protector of Buddhism and Buddhist rulers.” She added that “There were also legendary accounts of the barbarian-quelling powers of Bishamonten.” These became popular in both China and Japan. “Later a Japanese emperor, Kanmu 桓武, would install a monumental sculpture of Bishamonten in the upper story of Rajōmon 羅城門, the main gate to his new imperial capital, Heiankyō (the predecessor of Kyoto), which he had ordered built and occupied as the Emishi wars came to a close… [¶] This is an iconography that helps explain… why shrine-temple complexes and military outposts bear so many similarities, why pagodas, to name but one example, are reminiscent watch towers.”

Bishamon is the patron saint of (among others) priests, soldiers, doctors and missionaries – All of this makes sense. This god defends the faith, i.e, Buddhism, he is militant, at least, in costume, he wards off evil – which includes things that could harm one’s health – and as for missionaries, it is that faith thing again. This is a good time to remind you that Westerners are not so different. Onward Christian Soldiers…

Henri Joly, who didn’t always get things exactly right, cited Ernest Eitel about Bishamon in saying that “…he was canonized as God of Riches by Hiuen Tsung in 753, and plays an important part in exorcism.”

Boy dressed as Bishamon from a print by Chikanobu.

Boy dressed as Bishamon from a print by Chikanobu.

You say potato and I say Vaiśravaṇa, Vaishravana, Namtose, Kuvera, Jambhala, To-wen, Tamon, Bishamonten, etc.

Alice Getty tells the story of how the Buddha hid the youngest and favorite son of Hāritī, the ‘Stealer of Children’ under his begging bowl. The people of Rājagṛiha had begged Buddha for relief from this demon while she was away. When Hāritī returned she first started searching for the child she questioned all of her other 499 sons. None of them knew where Priyankara was. Hāritī grew increasingly desperate. Eventually she asked the great general Vaiśravaṇa (aka Bishamon) to help her. He told her to go back to Rājagṛiha and put her faith in the Buddha. As she approached Gautama appeared to her “…in a glory of light that surpassed the radiance of a thousand suns…” Buddha made her promise to quit eating the children of Rājagṛiha and when she agreed her son was restored to her. However, there was one problem. If she and her children had to give up cannibalism what would they eat? Getty tells us: The Buddha “…gave her a diet of pomegranates, the red fruit of which was supposed to resemble human flesh.”

Another connection with Vaiśravaṇa is Pāñchika, one of his 28 generals and the father of all of Hāritī’s children. Together this couple became a symbol of prosperity and wealth, at least, in the subcontinent. At times she holds a cornucopia and he holds a bag of jewels, but also a lance.

A Gandharan sculpture from the 2nd to 3rd century thought to represent Pāñchika and Hāritī. Note the cornucopia, another representation of abundance and wealth. © The Trustees of the British Museum

A Gandharan sculpture from the 2nd to 3rd century thought to represent Pāñchika and Hāritī. Note the cornucopia, another representation of abundance and wealth. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Her conversion to good also seems to have made a positive deity out of her and after that she became the patroness of little children. In Japan she is knows as Kishimojin (鬼子母神) or as Kariteimo. Below is a photo of another Gandharan sculpture of the goddess now in the British Museum. This image was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by PHGCOM.

In India Vaiśravaṇa (aka Kuvera aka Bishamon) was King of the North which also made him King of the Yakshas, the bringers of disease. His symbols were a banner, a mongoose (nakula) and the color yellow. As best I can tell so far the mongoose never made it into the Japanese iconography of Bishamon. Below is a bronze sculpture of Jambhala (aka Vaiśravaṇa) said to date from the 17th century. It is from the Bertsch collection and was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Clemensmarabu. Notice the mangoose crawling around the gods left arm. Below that is a photo of an Indian mangoose posted at the same location by J. M. Garg.

As Jambhala, the god of Wealth, his consort is Vasudhārā, Abundance.

Just in case you didn’t know, I didn’t, I looked it up – the plural of mongoose is mongooses. I think that’s great! An even more curious note: One source published in a book on Asian mythologies in 1932 says that the mongoose vomits pearls, another indication of riches.

Just in case you didn’t know, I didn’t, I looked it up – the plural of mongoose is mongooses. I think that’s great! An even more curious note: One source published in a book on Asian mythologies in 1932 says that the mongoose vomits pearls, another indication of riches.

Getty notes that “In Japan [Vaiśravaṇa] is worshipped under the name Bishamon, and is represented in armour ornamented with the seven precious jewels, and is generally standing on one or two demons. In his left hand he holds either a small shrine or the flaming pearl, while in his right is a jewelled lance.” The shrine is said to represent the Iron Tower in India where the Buddhist scriptures were found. Bishamon is often shown looking at the shrine as a symbol of him overseeing the treasures of that religion.

According to Getty Bishamon and Benten are the only 2 of the 7 Propitious Gods who are “…worshipped to any extent singly.”

So is he or isn’t he – a god of war, that is? There is no way to prove this one way or the other. So, I have decided to take a non-scientific poll of what scholars, pundits and blow-hards have said.

In 1902 Clarence Brownell referred to Bishamon as “the lucky god of War.”

In a 1906 volume of Kokka there is a one page entry entitled “Portrait of Bishamon-ten (The Indian Mars)”. Joly in 1906 identified Bishamon as one of the san-sen-jin (三戦神) or war gods. This figure he says is represented by a head with three faces riding on a boar.

August Karl Reischauer, Edwin O’s father, said he is in his Studies in Japanese Buddhism originally published in 1917. That same year Basil Stewart concurred, but added that Bishamon was also the god of glory. In another publication from 1917, A Desk-Book of Twenty-five thousand Words Frequently Mispronounced by Frank Vizetelly, Bishamon is placed right between bisexual and Bisharin, a Nubian tribe. The only reference to our deity is as “[Jap. god of war].”

Remember the Japanese also have Hachiman as a god of war.

On the other hand, L. Beatrice Thompson wrote in 1906 that “…in spite of Bishamon’s armour and ferocious aspect, he is not more especially the god of war than is Daikoku, and quite as much the god of riches as he…”

Bishamon as the god of wealth – A number of ancient Japanese texts say that Vaiśravaṇa is the same as Kuvera (sometimes Kubera) the ancient Hindu guardian of wealth. According to Chaudhuri “These writings projected the image of Vaiśravaṇa as a god of wealth to the common Japanese, in addition to that of a protector of the country. Thus he became a god of fortune.”

Tibetan gilded bronze from the 18th century of a bejeweled Kubera. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Chaudhuri also recounts the early 13th century story of a fasting [starving?] man who prayed to Bishamon for help. “A woman visited him and gave him a bowl with some rice in it Any rice taken from it was replenished immediately. For some unknown reason, the bowl became empty after a few months. When he prayed to Vaiśravaṇa again, the woman appeared once again and gave him a letter. She told the man to deliver it to a certain person. This person turned out to be an ogre. The ogre gave the man a bagful of rice. In this case also, the rice bag never emptied. The governor of the locality came to know about the bag and demanded it. The man couldn’t refuse But, the bag became empty in no time. When the embarrassed governor returned the bag, it regained its miraculous power.”

If you are going into battle it always helps to have Bishamon on your side – Bishamon appeared to Prince Shōtoku (聖徳太子: 574-627) in his struggle with the rebel Mononobe no Moriya (物部守屋: d. 587). The battle took place at Shigisan (信貴山) near Nara and the prince won. Fortresses were built on conquered territory and often temples dedicated to Bishamon were constructed there to guard against future assaults. Below is a photo of Mt. Shigi as posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Kenpei.

This god also showed up to bless Sakanoue no Tamuramaro (坂上田村麻呂: 758-811) before his assault on the Ainu. In thanks for his victory, he too built a temple, but this one is in a cave at Tokkoku (達谷窟). It, too, is dedicated to Bishamon. According to one source this was in 801 and included 108 statues of the god. Over the years the temple has been destroyed by fires, the last being in 1946. It was rebuilt in 1961 and is now said to contain 27 statues of Bishamon. Below is a photograph of the site posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Sapphire 123. Next to that is a detail image of the print made by Hasui in 1936 of that same site. It is one of my favorites Hasui prints. I have many.

It is said that in the 12th century when the Taira were vying with the Minamoto for control of Japan both sides were appealing to Bishamon for support. This, strangely enough, reminds me of contemporary football teams – either high school or college – praying for divine intervention. The winning side convinces itself that it has been shown celestial favoritism.

Vaiśravaṇa in China – In Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan by Chaudhuri it says: “Vaiśravaṇa acquired a special status in China around the eighth century. There is a legend saying that in 742, during the reign of the T’ang emperor Hsüan Tsung (685-762), Anhsi, the administrative centre of the western districts, came under a siege by Tibetan forces and their allies The Indian tantric monk Amoghavajra recited the Ninn-ō-gyō sutra to save the situation. Suddenly, a colossal figure of Vaiśravaṇa appeared in the sky and swept away the barbarian forces. He became known as Toupa P’ishamen (Jp. Tōbatsu Bishamon) and gained much popularity. A wood block picture of around the mid-eighth century found in Tung Huang shows him clad in armour and standing on the palms of a female figure.He holds a pagoda in one hand and a spear in another.This is most common image of Toupa P’ishamen… ”

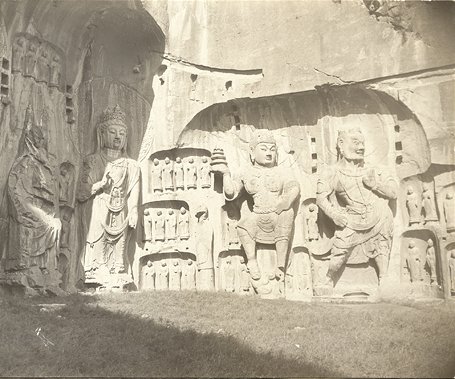

While we don’t have an image of that wood block print from Lung Men we do have a picture from those fine people at Harvard of a huge carved relief sculpture at the entry to cave 19. As best I can tell the fellow holding the pagoda is Bishamon.

This photo was taken between 1905-10 by Hayashi Kokichi and is in the archives of Langdon Warner at Harvard. © Harvard University

This photo was taken between 1905-10 by Hayashi Kokichi and is in the archives of Langdon Warner at Harvard. © Harvard University

The work at Lung Men (aka Longmen) began in 453. Below is a modern photo of the same scene taken by Fanghong and posted at commons.wikimedia.org. What you can’t see in this picture is that Bishamon’s right foot is resting on a quelled demon or yaksha. Below that is a fuller view of the setting from a photo taken by WikiLaurent and posted at the same site.

In the Tengu no dairi (天狗の内裏) or Palace of the Tengu Yoshitsune is described as a reincarnation of Bishamon.

Hey guys… Why don’t we get naked and have a religious festival? – First, I have to confess something: I don’t get rituals (or rites, in general). I don’t get marriages, funerals, confirmations, baptisms, bar or bat mitzvahs, wakes, circumcisions, etc. I don’t even get all the hoopla that goes with graduations or the end of the Oprah Show. How do these really differ from the Burning Man festivals or smoking peyote around a camp fire and communing with the spirits? But most of all I don’t get naked religious festivals. All they are are festivals without clothes. Call me a fuddy duddy, but I don’t even get the running of the bulls in Pamplona or La Tomatina Festival in Buñol.

Image from La Tomatina Festival in Spain, taken and posted by flydime at commons.wikimedia.org.

Image from La Tomatina Festival in Spain, taken and posted by flydime at commons.wikimedia.org.

Oh, sure, I get the point intellectually and understand the social needs to some degree, but overall… I just don’t get it. Now, you may be asking yourself “Where is he going with all this?” Well, I’ll tell you. While researching Bishamon I came across a couple of references to naked festivals that, as best I can tell, are held in his honor. However, if push came to shove, which it often does, I would say that it really just comes down to an excuse to get naked and jostle one another in a sweating, writhing mass and call it spiritual release.

In Windows on Japan – A Walk Through Place and Perception Bruce Roscoe gives a description of one such gathering at the Bishamon Hall at Fukōji Temple. “Women and men would fill Bishamon Hall on the third day after the New Year, undress, let their clothes fall aside and, bodies tight, push as a mass in one direction, then another, Bokushi Suzuki recorded. Women, some naked to the waist, wore only thin cotton. Men wore loincloths. ¶ The seven or so bouts of pushing were followed by a dance, after which a leader would say that a black cloud had descended in front of Bishamon. The crowd would ask what the cloud had come to say, and the leader would respond. ‘It came down to say that rice would rain.’ Sake was sprinkled over the heads of the crowd and the cups thrown into their midst. Good fortune visited those who managed to catch a cup. ¶ This was a dance for a bountiful rice harvest. No one had ever been hurt or molested in the pushing and nothing had ever been stolen from the clothing left on the floor, Suzuki reported. The dance… was never elevated to the status of a festival…” Later Roscoe notes: “The pushing ritual at Bishamon Hall has survived, the tourist office in Muika-machi confirmed for me, though in diluted form. It’s called Hadaka Oshiai Matsuri — ‘Naked Jostling Festival.’ Men still wear loincloths but on an all-male night that begins with junior high school students. Modestly attired women are able to participate during daylight hours. It is held 3 March at 6:30 p.m. Rice cakes have been added to the flight of sake containers.”

Roscoe added another point I was unaware of. He says Bishamon is “the deity that protects birds.”

Bishamon and the centipede 蜈蚣 or 百足 –

Bishamon’s messenger is the centipede or mukade. I don’t know why, but here you will learn more about me than you would care to know and in the past I would care to tell. I hate centipedes. They disgust me, but, I suppose, in the scheme of things they are just another one of God’s little creatures or in the Buddhist sense a soul transitioning through life. That said, below is a picture of one of these nasty little creatures which was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by L. Shyamal. While I am grateful that this image was posted at all – I appreciate nature shots – I think you should know that this is far from the one that I found the most disgusting, the kind that gives me nightmares.

There is a book from 1885 that recounts the encounters of various Western missionaries. In one account a writer talks about purchasing a small household shrine and a lantern which appears to have accompanied it. He calls the shrine “the poor man’s Bishamon” and says: “This same Mr. Bishamon resides within, and his horrid messenger [see I am not alone on this one] – the centipede – is painted on the doors, as it is on the lantern.”

Clearly I am not alone in my dislike of this insect. It was mentioned – and not in a good way – in the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest written record. I the Handbook of Japanese Mythology by Ashkenazi it says: “Centipedes are impure, polluted animals associated with the dead.” They were also mentioned in myths as gigantic, threatening creatures wrecking havoc wherever they were. Only the most heroic figures could defeat them. For instance, the archer Towara Toda, aka Hidesato (秀郷), destroyed one particularly malignant monster by wetting the point of his arrow with his own saliva. Gigantic, monstrous centipedes can only be defeated by great force combined with a little human spit. It is a known fact. Below is a Kuniyoshi from ca. 1845 in the British Museum Hidesato peering out at the Dragon Princess, Otohime, who has risen up from Lake Biwa. It is on loan from the Arthur R. Miller collection.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

T. Volker in his The Animal in Far East Art gives a variation on this story:

On the Seta bridge she met Fujiwara Hidesato (Tawara Toda). Him she recognised at once as the hero

sent by the gods to free Omi from the frightful terror. Him she implored to kill the mukade, to which he

assented. The same evening the hero arrived at the foot of the Mikamiyama where he perceived the

large body of the centipede twined round the mountain in seven coils. The eyes of the horrible being

burnt through the semi-darkness like two flaming moons. The intrepid hero shot four arrows in rapid

succession at the mukade but in vain, not one of them pierced the armour, all rebounded from the steellike

Seeing this he, on Oto hime’s advice wetted the head of the fifth with his spittle — human spittle is popularly

believed to be fatal to snakes, centipedes and creeping things in general — shot, and with this last arrow

pierced armour and body of the centipede. The next morning it was found dead at the foot of the mountain.

Deeply grateful Oto hime took Hidesato as a guest to her father’s palace. The dragon-king awarded him

suitably with a costly bell of bronze, a never ending bolt of brocade, an inexhaustible bag of rice and a kettle

that even without fire always held boiling water.

Another print by Kunisada, also in the British Museum, is a few years older than the Kuniyoshi. It shows Hidesato with his foot on the ‘neck’ of the giant centipede.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The Official Guide-book to Kyoto and the Allied Prefectures from 1895 gives a pretty good account of the encounter between Hidesato and the monster.

Hidesato was a famous warrior in the 10th century. A well-known legend says that once when he was

about to cross the bridge he saw an Immense serpent lying upon it. He did not hesitate but walked

directly over its body, when the serpent turned into a dwarf and said, “I am a dragon-god having my

home at the bottom of this lake. By Mikami Mountain lives my bitterest enemy, a huge centipede

whose long body winds seven times and a half about the mountain’s base, and that has often killed

members of my family. For many days I have been waiting for someone able to slay my enemy. I

beseech you to come to my aid.”

Hidesato followed the Dragon-king to palace. While there a great storm arose and all of the residents cried out in fear. Hidesato drew his bow, shot the centipede in the head – no mention of spit here – and killed it. “The dragon-king, grateful for the deliverance, presented him with many valuable gifts. Among them was the bell of Miidera.”

An 1893 edition of Outing says that Hidesato had the strength of 5 men and that “He… sank an arrow five feet in length up to the feather in the iron forehead of an enormous centipede, a fabulous creature that carried in each claw a flaming torch. When the arrow pierced the brain, the lights went out and the monster fell to earth with the noise of thunder.”

There is a wonderful early print in the Allen Memorial Museum by Kondō Kiyoharu (近藤清春: active 1705-30s) showing Towara Toda about to nail the giant insect monster. Roger Keyes notes that this is actually a calendar print. “The numerals for the long months are written at the upper left with a syllabic gloss mentioning the millipede. The numerals for the short months are concealed in the figure of the warrior.”

Ainsworth Bequest, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College

Ainsworth Bequest, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College

In Fiji (フィジー) in the 19th century a young warrior named Seru, the son of a chief, led a rebellion to seize power. After he succeeded one of the names he was given was Thikinovu, the Centipede, “…in allusion to the stealthy way in which that creature approaches, giving no notice of its presence until its formidable bite is felt.” A missionary and his family arrived close on the heels of the rebellion when the victors were eating their captives in celebration. “Two human bodies were in the ovens when Mr. Cross arrived…” Thikinovu’s missionary name was Ebenezer, but that didn’t stick for long.

In a novel by the Frenchman Eugene Sue (ウージェーヌ・シュー: 1804-57) there is a scene in which a waiter brings a customer a goblet of water with a large centipede in it. The customer is disgusted and refuses the drink. The waiter turns around and reaches into the goblet and pulls the centipede out with his fingers, turning back to the customer and says something like “There’s no centipede in there now.” Or so I have heard.

In Roughing It by Mark Twain (1835-1910: マーク・トウェイン) the humorist describes a luxuriant nap in the grass “…till you got a bite. A scorpion bite.” Then you would jump up and kill the it. Next you would bathe the bite with alcohol or brandy and then resolve not to sleep in the grass again. After a few more encounters with other unpleasant creatures you would go to bed “…and become a promenade for a centipede with forty-two legs on a side and every foot hot enough to burn a hole through a raw-ride. More soaking with alcohol, and a resolution to examine the bed before entering it, in future.” If you can’t read the subject line of the picture below the image it say “Reconnoitering.”

From Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov – “I am telling it. If I tell the whole truth just as it happened I shan’t spare myself. My first idea was a – Karamazov one. Once I was bitten by a centipede, brother, laid up a fortnight with fever from it.”

George M. Gould (1848-1922) wrote in his Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine: “There is a common superstition that centipedes have the faculty of entering the ear and penetrating the brain, causing death.”

Jean Webster (1876-1916) in Daddy-Long-Legs wrote: “This dormitory, owing to its age and ivy-covered walls, is full of centipedes. They are dreadful creatures. I’d rather find a tiger under the bed.”

In Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad (ジョゼフ・コンラッド: 1857-1924) a character lets out “…a few horrible screams… compelled to seek safety in flight from a legion of centipedes.”

The miracle of the pious holy man – Donald Keene recounts a story from The Tales of the Uji Collection which deals with another Bishamon miracle: “As a result of the many rigorous austerities which the priest performed, he was at length able, thanks to the magical powers he gained, to produce out of thin air a small image of Bishamon, of about the size that would fit into a miniature shrine. He built a small chapel in the mountains where he enshrined the image, and spent the years and months in practicing devotions of an unparalleled fervor.”

This Edo period gilded shrine of Bishamon standing atop a demon stands only 3.3″ tall. © The Trustees of the British Museum

This Edo period gilded shrine of Bishamon standing atop a demon stands only 3.3″ tall. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Kurama-dera 鞍馬寺 – Established northeast of Kyoto in 770 after the priest Gantei or Kantei (鑑禎) had a vision of Bishamon. Kurama means ‘horse-saddle’. In Practically Religious by Reader and Tanabe it says: “On the day of the tiger of the first month in the year 770 C.E., Gantei, a young Chinese priest who had come to Japan with the precepts master Ganjin (688-763), had a dream about a sacred place in the mountains to the north of Tōshōdaiji, where he was staying. He set out in search of it, but could not find it until a white horse with a jeweled saddle appeared and showed him the way. Finding a level spot just below the summit, he made a fire to spend the night only to be attacked by a female devil spitting poison. After failing to kill the devil even though he stabbed it with his staff, Gantei hid beneath a large dead tree, which, because he recited a mantra with all his might, toppled over onto the devil and killed it. The next day the tree transformed itself into a statue of Bishamonten, guardian of the north and subduer of devils. Gantei built a hut to enshrine it, and this was the beginning of Kuramadera, Temple of the Saddled Horse. An annual festival is still held on the first day of the tiger (hatsutora) -a day on which, according to one of the temple’s brochures, people have come for ages ‘to pray for the realization of their deepest wishes, prosperous business and happiness.’ ”

This photo was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Axel Ebert.

This photo was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Axel Ebert.

In 796 Fujiwara Isendo had a dream about finding a statue of Kannon north of Kyoto. Not knowing where to look he saddled up his white horse and set it loose following its tracks. “The horse led him to the Bishmonten hut on Kurama, but Isendo was puzzled and disappointed since he had still not found Kannon. That night a sixteen-year-old boy (that is, Maō) appeared in his dream and told him that Bishamonten and Kannon were two different names for the same deity. Isendo went back up to the mountain and built a temple in which he enshrined the Bishamonten image and a newly made statue of a thousand-armed Kannon. ¶ The three deities who appear in the legend of Kuramadera – Maō, Bishamonten, and Kannon — are worshiped together as Son- ten, the Exalted Divinity comprised of three forms merged into one essence. Bishamonten represents the light of the sun, Kannon the love of the moon, and Maō the power of the earth. As a single triune deity Sonten is the great spirit and energy of the entire universe and the foundation of the existence of all things. Harmony of the universe is an important teaching of Kuramadera…”

Chaudhuri says that Sakanoue no Tamuramaro came to pray at Kuramadera before setting out to fight the Ainu. After he won he came back and presented his sword to the temple in appreciation. Supposedly, it remains a temple treasure to this day.

There is an annual “Bamboo-cutting Festival” or Takekiri e-shiki there on June 20 (by today’s calendar). It is a small ceremony said to go back 1,000 years. A priest defeated two evil serpents with Bishamon’s help. Now “…eight priests dressed in robes and hoods of yamabushi (mountain priests) form two teams and race to hack to pieces four lengths of green bamboo that symbolise the serpents. The festival begins at 2 pm.”

Shitennō – the Masters of their Domains

The Shitennō 四天王 are the Four Heavenly Guardian Kings comprised of Dhṛtarāṣṭṛa, Virūdhaka, Virūpākṣa, and Vaiśravaṇa. They rule over each of the cardinal directions. Bishamon’s domain is the north.

In Hepburn’s 1905 Japanese-English dictionary, not the earliest, he defines Shitennō as “The four demon kings who guard the world against the attacks of Asuras.” His use of the term ‘demon’ to describe the guardians is interesting since asuras are another form of demons or ‘Titans’ which plagued the world. The asuras have also been described as ‘inferior deities’ or as being like fallen angels. In some cases they are reported to be more powerful than the yakshas mentioned above.

So, what is it that is so important about the direction north?

W. G Aston in his Shinto: The Way of the Gods says: “In all the more modern megalithic tombs the entrance faces the south. This arrangement is connected with the idea, common to the Japanese with the Chinese and other far-eastern races, that the north is the most honourable quarter. The Mikado, on state occasions, on the north side of the Hall of Audience. His palace fronts the south. Immediately after death corpses are laid with the head to the north, a position scrupulously avoided by many Japanese for sleep. They say they are unworthy of so great honour.”

In Asiatic Mythology 1932 it says: “The Buddha then goes on his way toward Kusinagara; he halts in the wood of the two ṣāla-trees. Knowing that his hour is come, he requests Ananda to ‘place the couch of the Tathāgata between the two ṣāla-trees, with the head to the North…”

In the same book even numbers and North are said to be yin elements which are always stronger than yang ones.

In an account of missionary life in China published in 1885 there is a curious passage: “He [the landlord] would no doubt have objected strongly to a window in the north wall, as all the bad influences are supposed to emanate from this quarter. The universal prevalence of this belief is well illustrated in this city by the fact that in almost every house here that I have seen, the best rooms are built with an aspect due south, and there are never any windows in the north wall.”

A question I hope to answer in time: Why is it that Bishamon is the only one of the Four Heavenly Kings which was made on of the 7 Propitious Gods? Why? What is wrong with the others? Surely someone has an answer somewhere.

I have it (maybe)! According to one web site, which citied a book I don’t have access to (yet), in 1623 Tokugawa Iemitsu (徳川家光: 1604-51) asked the priest Tenkei to name the virtues of nobility. Tenkei said there are seven. He was then asked which of the gods best represented each of these virtues and it was Tenkei that gave us the group we know of today. However, other sources say the first mention of the ‘Seven Lucky Gods’ was from 1420 when a procession was held at “‘a place called Fishimi”. Another story from the last half of the 15th century tells of a group of enterprising con-men who dressed themselves up as these gods and then preyed on the gullible.

It should also be noted that these ‘virtues’ are not linked to morality, but are more closely tied to qualities one would want to possess. That is why a long life, wealth and popularity are included in this list. Since when is popularity moral or wealth or a long life. Of course, the Protestant ethic links success in life to one of God’s blessings, but still… And popularity? Just ask any Hollywood celeb where they rank on the morality scale. Confucian virtues are tied to morality, but they are Chinese and not necessarily Japanese – something you knew already.

Just for good measure and because it is so damned impressive here is a detail from a hanging scroll by Hanabusa Ikkei in the collection of the British Museum. From ca. 1832 when the artist was close to 80 it shows a four-head Bishamon astride a lion. I count 12 arms. Eight are holding swords and the others hold among other things jewels and a pagoda.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

How does one choose a favorite god? In Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005 Patricia Graham says: “Cultlike devotion to particular persona has always been a part of Buddhist worship in Japan. Worshipers self-select personal saviors from among the Buddhist, Shinto, Confucian, and Daoist pantheon, based on personal attraction to legends asserting the effectiveness of these figures’ miraculous powers, often as channeled through the medium of renowned images that represented them…” Graham then mentions another category of ‘faddish deities’. “Yet among these newly popular fashionable deities of the Edo period, one group, the Seven Gods of Good Fortune, a powerful new configuration of divine guardians assembled from various faiths… because they stand out from the others due to their enduring appeal.”

Dr. Graham’s time-line for these gods differs somewhat from the one sketched above. She says that the first to assemblages of 2, 3 or 5 of them appeared in the late 15th century. “Probably only in the second half of the seventeenth century did the conception of the set of seven deities of good fortune coalesce.” She also notes that the earliest published attempt to standardize the iconography from 1690 includes a list with Bishamonten among the seven, but replaces one of the gods with a Shōjō, ‘…a sea-dwelling, red-haired, and a perennially jovial monkey-faced figure…” By the 1783 edition the set of seven had been codified. She also notes that “…the personification of good fortune has its origins in Chinese folk religion.” As for the choice of seven as the number of gods to be honored Graham is skeptical of the Tenkai/Iemitsu account since there is nothing in the known writings of priest that time him to this story.

Why the number 7? Several authors make references to the Japanese and the significance of the number 7. I have yet to confirm some of these citations, but until I do here are a few of them: Japan originally had 7 provinces; there are 7 treasures to go with the 7 gods; “Japanese Buddhists believe people are reincarnated only seven times”; there are 7 weeks of mourning after a person dies; there are 7 autumn flowers and 7 spring herbs.

The only time I ever was with a group using a ouija board they would ask questions like “How many wars has the United States been in?” and would then turn to me to see if the board was right. I would always make the number fit the board’s answers. They were convinced. I wasn’t.

The first Japanese woodblock image ever created was a figure of Bishamon. It is dated to the year 1162 and was found inside a statue of Buddha. Currently it is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. See below.

For more information about Japanese prints and culture please visit our other web site at http://www.printsofjapan.com/.

[…] More historical background is given in The Seven Propitious Gods: Bishamonten – Wealth or War – Which is it?: […]

Pingback by Bishamon(ten) and why paper tigers are placed around Chougosonshi-ji Temple | JAPANESE MYTHOLOGY & FOLKLORE — April 1, 2014 @ 10:11 am |

Enjoy your collection of artwork on the Bishamon and Daikoku pages. As for why Bishamon was the only one of the Four Heavenly Kings who was inducted into the Seven Lucky Gods. ……………. In early Japan, the Four Heavenly Kings rose to great prominence in rites to safeguard the Japanese nation. In later centuries, however, Tamonten became the object of an independent cult, supplanting the other three in importance. When worshipped independently, he is called Bishamonten (or Bishamon, Bishamon Tennō, Tobatsu Bishamon), but when portrayed among the Shitennō (Four Heavenly Kings) he is called Tamonten. For much more, see my web site at http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/bishamonten.shtml

Comment by Mark Schumacher — October 27, 2015 @ 11:02 pm |