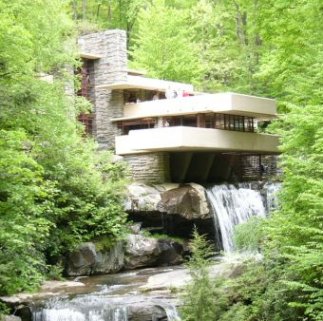

As a child I dreamt about fantastic architectural settings. Sometimes awake, sometimes asleep. While the nightmares were like Piranesi’s prisons the dreamier daytime musings included everything from the 1937 house at Falling Water by Wright to the 1929 Barcelona Pavillion by Mies. My favorites were distinctly planar surfaces – both horizontal and vertical – married to bodies of water – either flowing or quiescent. (Below are images of both so you will have a better idea of what I am talking about. The first is by Serinde while the second is by Vicens. They are posted at http://commons.wikimedia.org/ and have been placed in the public domain.)

It wasn’t until decades later that I discovered the shrine at Itsukushima. Equally as sublime and exciting as the structures shown above – but with one exception: It predates our 20th century masterpieces by nearly 900 years. For me Itsukushima is beauty itself which is as iconic as the Venus de Milo. Placed in a small inlet during high tide the shrine seems to float on the water. To call it exquisite and ethereal may not even be good enough.

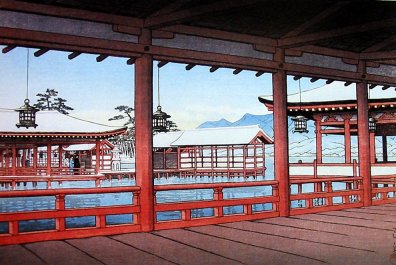

Below is a detail from a print by Hasui followed by a photo of one of its corridors posted by Fg2 also at commons.wikimedia.org.

Shinden-zukuri (寝殿造り) – A Heian architectural style: It is curious that the Itsukushima Shrine is the finest surviving example of the shinden-zukuri style. No matter what source material one reads shinden-zukuri is always described as the style used for palaces and mansions and no one ever seems to mention Shinto structures. Coaldrake in his Architecture and Authority in Japan drives home the point that this was a style which reinforced the power of a small elite ruling class. Of course, this makes perfect sense because even today size and expensive outlays matter. There are very few McMansions in the ghetto. At least the Japanese had the good taste so lacking in contemporary (Vegas/Dallas) garish.

The Tale of Genji exists wholly within a shinden-zukuri world. When the prince wasn’t traveling between shinden-zukuri structures he was sitting or reclining in one or was flirting and amorously pursuing his next affair in one of its gardens. And this is an important point because this was an architectural form which “…transcend[ed] the limitations of time and space…” Each building “…was an organic part of [its] garden landscape.” The effect was heightened by the fact that there were few permanent walls. There was no clear distinction between the exterior and the interior. Everything was a part of the whole. These structures represented a time of peace and serenity. Only harsh weather made their living conditions problematical. On the other side, a warm spring day with a gently wafting breeze, the smells of flowers and nature, a gentle falling rain… What could be more perfect?

Myth (神話): It is said that it was forbidden to give birth or to die on the island of Delos (デロス) since it was sacred ground where Apollo (アポロ) was born. However, archeological remains of make it clear that once there were thriving communities there. Today the island is uninhabited and lacking most modern amenities with almost no shelter from the sun and no lodgings. It lies smack in the center of a group of islands we call the Cyclades. They got their name because they formed a circle around Delos. Below is a photo of Delos posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Vijinn.

Like Delos Miyajima (宮島) is also sacred territory and Itsukushima sits snugly in one of its inlets. Some say the island was so rich in gods that no mortal was allowed to set foot there. Others say no ordinary mortal could do so. That is why the Shinto shrine at Itkushima is built over the water and not the land. That way visitors could make the pilgrimage to Miyajima without ever desecrating the island itself. Compare the image of Delos with a photo taken by Kezeru – also posted at wikimedia.org – from the top of one of Miyajima’s mountains.

The shrine is dedicated to three female deities, the daughters (sort of) of Susanoo no Mikoto (須佐之男の尊): Ichikishima Hime no Mikoto (市杵島姫神), Tagitsu Hime no Mikoto (湍津姫神) and Tagori Hime no Mikoto (田心姫神). Let me explain: In the Kojiki (古事記), the most ancient written account in Japanese, it says that there is a face-off between Amaterasu (天照), the Sun goddess, and her brother Susanoo. This was a sibling rivalry which gave true meaning to the term sibling rivalry. Both want off-spring. So, Amaterasu – incidentally the great-great-great-great… (you fill in the greats) grandmother of the current emperor) – asks her brother for his sword. She breaks it into three pieces, washes them off, chews up the pieces and spits them out. “Into the misty spray there came into existence…” the three deities to whom the Itsukushima shrine is dedicated. Since the sword was that of Susanoo these goddesses are considered his daughters. He, on the other hand, spits out his sisters jewels and voilá five sons are born, but that is another story.

Basil Hall Chamberlain in his translation of the Kojikitells us that Ichikishima Hime no Mikoto translates as Lovely-Island-Princess. In a footnote he tells us that ichiki is “an unusual form of itsuki…” which is the true name of the island in the Inland Sea which we know through common parlance as Miyajima or ‘Temple Island’. Jim Breen tells us that miya can mean either a Shinto shrine or a princess.

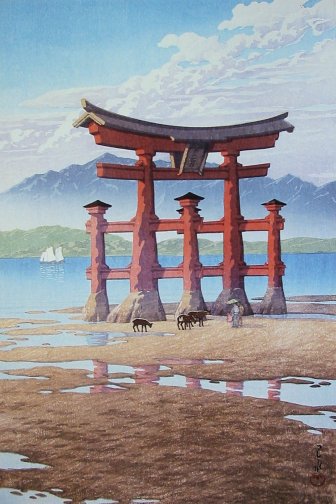

One more point before we leave the myth section – and I may be stretching it here: The magnificent torii (鳥居) which is set dramatically in the water 220 yards from the shrine. (Torii literally means ‘bird perch’.) It serves as the entrance and must hold mythical significance itself. It stands 52′ tall overall while the main posts are 44′ each and are created from individual camphor trees. The hollowed out cross-beam is 76′ long. There is hardly a more impressive sight in all of Japan.

It is the camphor tree posts which fascinate me. In Japan kami (神) – loosely translated as gods – inhabit just about everything both animate and inanimate. Trees are not exempted. All over Japan there are famous trees marked off as possessed by kami. The camphor trees must have been chosen for their special spiritual properties. Below are three images: The first was posted at wikimedia.org by Kerazu. If you look closely you will notice the unfinished nature of the shape of the main posts. They appear to be the trees stripped of their bark and then lacquered. The second image is from another Hasui print. He must have really loved this place because he created so many different woodblock prints of it. The third, also found at wikimedia.org, is by Sanjo and shows a magnificent, living camphor tree from Kagoshima.

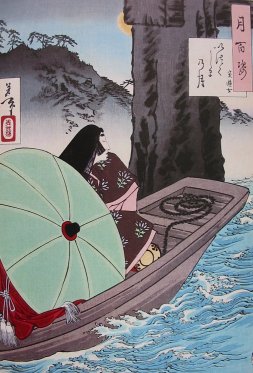

There is a series of prints by Yoshitoshi (芳年), initially published between 1885-92, entitled “100 Views of the Moon”. Some of the scenes are not easily recognizable like that of the Heian style woman in a boat at the base of the torii at Itsukushima. John Stevenson noted when describing this print that “…the vertical pillars which were constructed of rough tree trunks, an unusual feature of this great torii.”

History:There is not a lot of historical information to be found on Itsukushima in English, but there are a few seminal points.

The shrine was established in the late 7th century under the tutelage of the Saeki clan. We don’t know what it looked like then, but it definitely was different in many ways from what we know it to be today. By the late Heian period this area had come under the control of Taira no Kiyomori (平清盛), one of the most important figures in 12th century Japan if not of all time. Without giving a full biography which can be dealt with better in future posts it is important to know that Kiyomori had been made governor of Aki province in 1146. From here he built his power base partially because he controlled most of the trade with Sung China. Itsukushima became his primary shrine and he its patron. It is Kiyomori who had the shrine rebuilt in the form we know today.

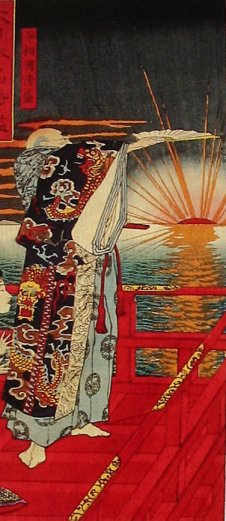

Kiyomori has not always gotten the best press. Perhaps if his side had won things would be different. Supremely egotistical and probably a bit mad he, nevertheless deserves a fair amount of attention. Brought up in the ranks he came to dominate the government in Kyoto for more than 20 years. He even manouevered getting his grandson Antoku (安徳) named emperor. Below is a detail of a print by Yoshitoshi – who was a bit mad himself – showing Kiyomori ordering the sun to stand still so his workmen can finish construction on his shrine. Itsukushima?

Over the next few years the Taira clan donated numerous precious gifts to the shrine including a special suit of armor – the militaristic – and a wonderful set of scrolls illustrating the Lotus sutra – the Buddhistic/otherworldly realm. It would seem they left no base uncovered. There is a story that while Kiyomori was staying at the shrine he was visited one night while he was sleeping by two representatives of the goddess Benten (弁天). They presented Kiyomori with a special sword. When he woke up there was a real sword lying next to him. The next night he was visited by Benter herself and she told him that as long as he was righteous his clan would be successful. But if he strayed calamity would befall his heirs. He strayed. (This story must have been written by his enemies.)

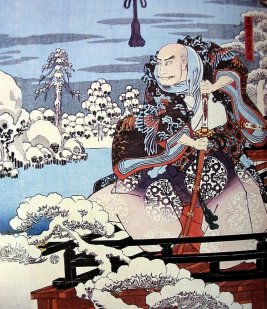

When he was in his prime Kiyomori tried to move the capital from Kyoto to Fukuharakyō, near Kōbe, where he already had a major estate and had built a magnificent residence. Hiroshige portrayed him there in a winter landscape as mad as any Shakesperean tragic character. In this detail he imagines that he can see the skeletons and skulls of his dead enemies come back to haunt him.

Now lets move forward a few centuries to 1598 when one of the greatest Japanese artists, Kaiho Yūshō (海北友松), of all time traveled to Itsukushima to view the Lotus sutra scrolls donated by the Taira clan. Four years later Sotatsu (宗達), perhaps Kaiho’s student, another one of my favorite, favorite artists, was sent to Miyajima to restore these scrolls. What is most significant about this date is that it may be the first solid information we have about Sotatsu – and it is connected, if only, tendentiously with Itsukushima. Below is a detail from a poster advertising a major Sotatsu exhibition. It reproduces two of the most famous screens ever created. The figures represent the wind and thunder gods.

It wasn’t until the 1770s that the shrine was represented in a woodblock print by Utagawa Toyoharu (歌川豊春). It shows a festival there and there is a copy in the British Museum. There weren’t even many print images of this beautiful shrine in the 19th century. The only reason I can figure is because it was so far off the beaten path and it was relatively difficult to travel in those days – especially before the Meiji Restoration.

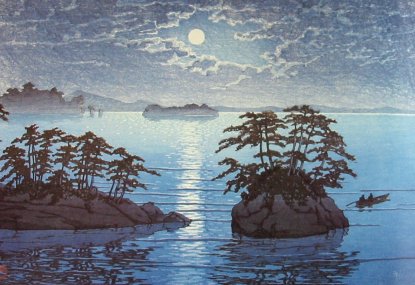

The Nihon Sankei (日本三景) – The Three Most Beautiful Sites in Japan: Hundreds of years ago the Nihon sankei were codified as a grouping. One source says it was 400 years ago while Frommer’s Japan credits Bashō (芭蕉 1644-94) 130 years later. These included two locations known for their natural physical beauty, Matsushima (松島) and Ama no Hashidate (天橋立), and the man-made structures of Itsukushima shrine. Matsushima which literally means ‘Isle of pines’ (or ‘Pine Islands’, if you like) is located along the eastern coast of northern Honshu and was already famous at the time of the writing of The Tale of Genji in the 11th century and is mentioned in its poems. According to Frommer’s there are more than 260 pine clad islands in this bay. (One cautionary note: Many writers talk about the industrial shoreline spoiling the views and others about the large number of motor boats tooling around these scenic isles.) Below is a detail of a 1933 print by Hasui showing Futagojima at Matsushima. Below that is a photo by Christian Gunther and generously placed in the public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org.

The third member of this beautiful trio is Amanohashidate or Hashidate – same as Ama no Hasidate – located on the west coast of Honshu in the Kyoto prefecture. Known as the ‘Bridge to Heaven’ it is actually a sand spit 3.6 kilometers long heavily populated with pine trees. Several contemporary guide books suggest that visitors climb the hills on either side, spread their legs, bend over and look between them to get a sense of how this location got its name. There are other variations on this manoeuver, but they are all rather sanitized versions of an older tradition which says that there was once a group of visiting aristocratic women. One of them had to relieve herself so she went off a bit, squatted down and did what she had to. While in this position she leaned forward and looked back between her legs. It was then she realized that this spit of sand looked like a ‘Bridge to Heaven’. Personally I find this explanation a bit contrived and a little hard to believe, but it took me forever to believe in continental drift. So, what do I know?

The first image shown below is a detail from a print by Hiroshige (広重) and the photo is by SElefant posted at wikimedia.org.

Weather or not – natural and human vicissitudes: The shrine at Itsukushima has suffered over the centuries from man made and natural disasters. In early September 2004 Typhoon Songda hit the region and the BBC quoted one official at the shrine saying: “There is damage from both water and wind. The damage is so large that I’m dumbfounded…” Strong quakes – strong enough to bring down buildings and kill huge numbers of people – strike the region periodically. Fire is always a threat – especially when you consider that the roof of Shinto shrines is made up of layers of cypress or hinoki bark (hiwada 桧皮). The first image below is a detail shot by Fg2 at commons.wikimedia.org of a temple in Kyoto, but not dissimilar from that at Itsukushima. The second photo shows more of the Kyoto roof.

For more information about Japanese prints and culture please visit our other web site at http://www.printsofjapan.com/.

Hello,

Seems like it’s been a while since you write this post, but I recently discovered it while looking for some info about Miyajima, its shrine and the torii.

I find your post very rich and so enlightning, i learned a lot and now I’m able to continue searching for new things to complete my self-guide to visit the place in august.

Best whishes from Barcelona,

Ys.

Comment by Ysondra — June 19, 2013 @ 9:20 am |